“To govern is to choose, however difficult the choices may be.”

—Pierre Mendès France, prime minister of France 1954–’55

If you want to understand where Joe Biden’s presidency went wrong, when his administration stopped looking like Barack Obama’s and started looking like Jimmy Carter’s, you could start with the failure of Build Back Better.

Build Back Better was a sweeping agenda of economic reform on the scale of the New Deal, meant to solidify its author as the “FDR-sized” president he wanted to be.

Dusting the text off now, you can feel that ambition. Across two bills — the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan — it sought to spend over $4 trillion across a decade on transportation, manufacturing and science, home care, clean energy, an expanded child tax credit, tuition-free community college, child care, and much more. It would have been an epochal expansion of government spending and ambition, on par with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal or Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society.

Little of this became law, of course. The bipartisan infrastructure law enacted in 2021 included $250 billion in new transportation spending, less than half of the Jobs Plans’ number; even adding the $72 billion in the Inflation Reduction Act for electric vehicles doesn’t close the gap much. While the Jobs Plan included $1.6 trillion in climate spending, the Inflation Reduction Act’s climate measures are estimated to cost less than half that much. The CHIPS and Science Act passed in 2022 appropriated all of $79 billion to support manufacturing, a far cry from Biden’s $590 billion bid, and largely didn’t appropriate money for science at all. And then there’s the American Families Plan, almost all of which fell by the wayside, not passed by Congress in any form.

That Biden was not able to pass the maximal version of his agenda is not much of an indictment. No president passes everything they want. They have to prioritize, to choose which parts of the agenda are worthy of their political capital and effort and which are not. Immigration activists were furious that Obama didn’t prioritize comprehensive reform in his first term, and unions were mad that he didn’t do the same for labor law. He put health care first, which yielded fruit for him — as it had not for Bill Clinton, whose choice to do the same in 1993 resulted in calamity.

But in both cases, the president and his allies in Congress made a conscious choice, for good or ill. What stands out about Biden is the degree to which he simply refused to choose at all.

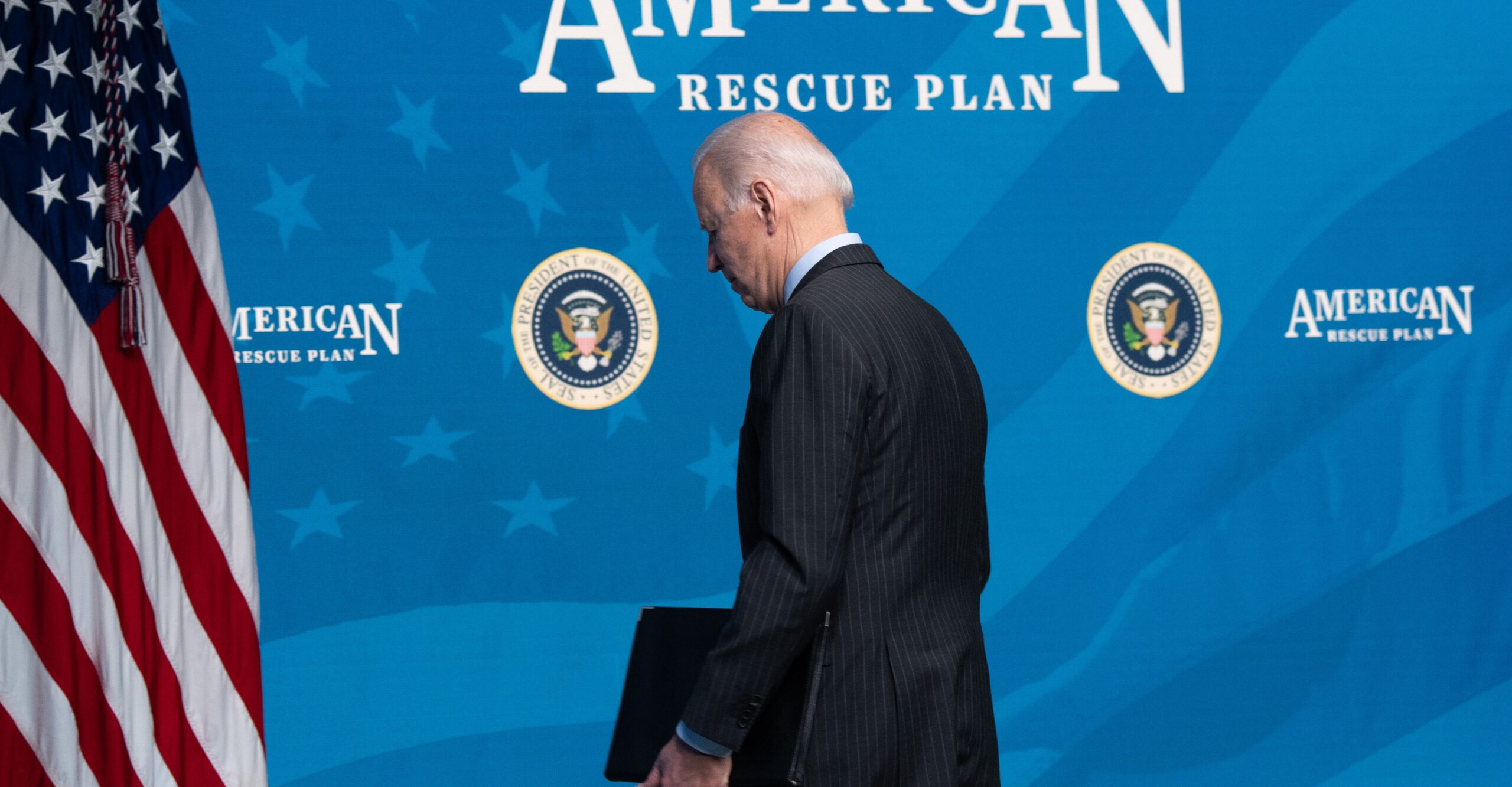

From the design of the American Rescue Plan at the beginning of his term, through Build Back Better and the rocky implementation of the measures he was able to pass, Biden’s domestic record is characterized by a refusal to prioritize, a paralyzing fear of pissing off any Democratic faction that too often wound up winning nothing for any of them.

Multiple causes, including his advanced age, conspired to make him the weakest chief executive America has had in decades. He won his nomination in 2020 through a strange primary that left him leery of intra-group conflict. His advisers, a group of courtiers drawn heavily from his own family and longtime Senate aides, shared this distaste for infighting, and were leery of offending the boss. All this was compounded by his temperament and the approach to politics Biden has had his whole career.

The result is a failed presidency that left Biden without much of an enduring domestic policy legacy and made what accomplishments he can claim immensely vulnerable to the Republican trifecta taking over the government he led.

It’s a rather undignified end to the career of one of America’s longest-serving statesmen. One would think that a 44-year veteran of the Senate would do well precisely at the part of the presidency that demands strong leadership over the legislative process — and indeed, that was a major part of Biden’s case for himself in 2020.

But the legislative process that could have shepherded his agenda into law is exactly where Bidenism fell apart.

Failure at conception

Biden’s missteps began at the very beginning, with legislation sometimes billed as a precursor and sometimes as a part of Build Back Better: the American Rescue Plan.

The $1.9 trillion bill, signed into law less than two months after Biden’s inauguration, was in some ways a triumph. It was markedly larger than the 2009 stimulus passed by his former boss. Whereas Obama’s stimulus proved inadequate to the task of returning employment to pre-financial crisis levels, Biden’s stimulus succeeded in bringing down unemployment incredibly rapidly, returning economic growth to its pre-pandemic trend.

But it also was a direct cause of the 2022 and 2023 inflation, price hikes that in retrospect contributed to Donald Trump’s eventual victory in 2024. Exactly how much inflation the law caused is debatable, but one group of economists compared the US experience to that of European countries with less ambitious stimulus programs and attributed about 3 percentage points of inflation to excessive stimulus.

Given that the inflation measure the economists used peaked at 6.6 percent, that implies that without the bill’s pressures, overall price increases could have been reduced, perhaps even halved.

That wouldn’t have just helped avoid a Trump comeback — it possibly would have been better for workers. Inflation was high enough that the median worker saw incredibly weak wage growth, certainly weaker than under Trump or Obama’s second term. A more moderate stimulus, like the $618 billion package proposed by a group of Republican senators in February 2021, could have returned employment to high levels without putting as much pressure on prices.

So how did the Biden team let this happen, especially when Democratic heavyweights like Larry Summers were warning them that the stimulus was too big?

I’m not in the best position to judge; I cheered on the American Rescue Plan as it happened, thinking the risks of overheating were smaller than the risks of being too meek. But I was wrong, and it’s worth asking how policymakers like Biden got this wrong too.

Biden expressed fear that the package was too big as it was being debated. In mid-December 2020, Frank Foer reports in his book The Last Politician, Biden’s aides presented him with a $2.4 trillion proposal, including both stimulus measures and longer-term infrastructure and child care spending. Biden balked at the price tag, saying, “I don’t want to be dead on arrival,” and fearing Republican backlash.

Biden had his soon-to-be Chief of Staff Ron Klain pass along a $1.3 trillion plan to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, who balked, arguing something closer to $2 trillion was necessary. Why?

“As he cut deals with the Trump administration, Schumer kept a mental tally of the pent-up demands of Democratic senators, all the measures that never made it into previous iterations of Covid relief packages,” Foer writes. “As soon as he heard Biden’s number, he knew it wasn’t big enough to cover them all.”

In other words, neither Biden nor Schumer, even at this early moment, were interested in setting priorities and crafting the bill deliberately. They had demands from Schumer’s members and would include them.

Biden folded. His initial skepticism faded. He deferred to his Senate leader.

That approach worked well enough. After dual victories in Georgia Senate races on January 5, Democrats had a one-vote Senate majority. They rebuffed the $618 billion offered by moderate Republicans and charged ahead.

But as they crafted the package, Biden and his allies didn’t stop and ask: Which of these measures is the most important? Which are the most potentially inflationary? Should we include provisions that would dial back or expand aid, depending on what happens with unemployment and inflation?

It was the first indication of what a president who refuses to choose looks like.

Build Back Bungled

The “just write a wish list and pass it through” approach would not work for Build Back Better.

Like the American Rescue Plan, BBB was less a coherent agenda than a hodgepodge of different priorities with their own congressional champions. There was the child tax credit expansion from the American Rescue Plan, which advocates like Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) wanted to make permanent; there was universal pre-K, paid leave, and child care, which Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) championed; there were clean energy credits, which climate advocates like Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) prioritized; and much more. None of them, in other words, were specifically Biden’s signature issues.

It was obvious from the start that not all of this could pass. Democrats never had a majority for this full agenda, and their majority was dependent on moderate Sens. Joe Manchin (WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (AZ) — then both Democrats, today both independents. These two had to be wooed for any measure to earn majority support in Congress.

There’s a tendency among left-leaning observers to see Manchin and Sinema as hopelessly unpredictable, or even bad-faith negotiators, but both of them were clear throughout the process about what they wanted. Frustratingly for the administration, the two senators’ desires were at cross purposes. Manchin was open to tax hikes on the rich but skeptical of the child tax credit and other “handouts,” while Sinema was open to those programs but hostile to tax hikes. Manchin was also, crucially, insistent that the package not play numbers games to seem cheaper than it was: Instead of temporarily extending programs that were meant to be made permanent eventually, any changes to safety net programs should be enacted permanently from the start.

There was an obvious way to square this circle: pass a relatively modest bill funded by revenue that Sinema could support. Indeed, this was what in fact happened in August 2022, when Manchin negotiated the Inflation Reduction Act with Schumer. But was that package of energy tax credits and prescription drug controls the best that the Democratic majority could have done? Or could a more competent administration have passed a package that included something bigger, and permanent, for working families?

There are many indications that congressional leadership and the Biden administration badly bungled these negotiations. In mid-2021, Biden invited Manchin, Sinema, and a number of centrist House Democrats to the White House. According to Jonathan Martin and Alex Burns’s book This Will Not Pass, Biden announced to the group that Sinema had stated that the maximum Build Back Better bill she’d support would cost $1.1 trillion. Sinema was furious at Biden for betraying what she said was a “private conversation.” Biden then had to convince a senator whose vote he desperately needed not to leave the room.

But the more telling error in that meeting was something else: “Each of you are saying, ‘Do fewer things and do them bigger,’ but you’re all saying different things,” Biden told the group of moderates, per Foer. “And if you add up all your different things, it’s actually a pretty big number. If you add all this up, it’s well over $2 trillion.”

The advice Biden was getting was good. Build Back Better was trying to do too much, and in so doing, failed to do any one thing well or permanently. But his takeaway from this was that trying to do one thing well was a trap, because someone would still be mad at him for not doing their thing permanently.

This failure to make a choice, to decide what to prioritize and make the centerpiece of Build Back Better, was Biden’s greatest legislative mistake as president. It represented a profound failure of leadership. In that situation, it was precisely Biden’s job to state what one or two things out of the package he’d like to do permanently. Perhaps it was the child tax credit; then he could negotiate a deal with Manchin that addressed the latter’s concerns about work incentives. Perhaps it was universal pre-K. Perhaps it was the clean energy credits. But he had to decide — and Biden was a man who could not choose.

This indecision repeatedly disrupted talks with Manchin. After negotiations in late October 2021 between Biden, Schumer, and Manchin, the trio agreed to remove paid leave from the package to reduce its size. Then the House passed a version of the legislation that included paid leave anyway. “Manchin’s allies say he was frustrated by the feeling that a concession in his direction, once agreed to, could later be rescinded,” the Washington Post’s Jeff Stein and Tyler Pager would report.

Then, a few days later, Biden announced a Build Back Better framework that was full of the temporary measures Manchin had been arguing against. Manchin made his displeasure clear soon thereafter, but to win over progressives in the House for an infrastructure bill, Biden told them that Manchin was on board, when he’d made no such commitment.

The greatest missed opportunity of the whole debacle, though, was a framework Manchin presented in December 2021. The $1.8 trillion plan included $500 billion to $600 billion in climate spending (in the ballpark of what the Inflation Reduction Act would eventually include), plus 10 years of universal pre-K, and it extended the American Rescue Plan’s expanded Affordable Care Act subsidies for health insurance.

Biden did not take the deal as it was, which was fair. It’s a negotiation, after all. Instead, the White House issued a press release singling Manchin out for blame in holding up the package. Manchin had urged them not to do this before the release went out, but it went out anyway. He announced he was abandoning the effort. The White House, in a fit of pique, sent out a remarkably pointless and petty release of their own accusing Manchin of operating in bad faith.

Was the $1.8 trillion package the White House threw away perfect? No. It excluded the child tax credit entirely, and if I had my druthers, that proposal, with its transformative antipoverty impact, would’ve been substituted in for universal pre-K.

But the thing is that I did not get my druthers, and neither did Joe Biden. Joe Manchin did. That’s how the Senate, and the basic arithmetic of getting to 50, works. Biden could not control who the people of West Virginia elect, but he could choose how to respond to the person they elected. And the $1.8 trillion plan was certainly better, and did more for children, than the Inflation Reduction Act would a year later.

Talks would not be revived for months, and only then under Schumer’s auspices, with the White House far away. With the Biden administration at a distance, the Inflation Reduction Act was able to come together. Schumer was often as wavering as Biden in 2021, and deserves blame for those failures too. But he redeemed himself a year later by cutting a final deal.

There’s perhaps no more damning critique of the White House’s legislative strategy than the fact that a bill only came together when they got out of the way. Someone, it turns out, could choose: It just happened to be Joe Manchin, not the president.

Why?

Perhaps it feels like I’m being unfair to Biden. He did, after all, sign not only the American Rescue Plan (which, for all its flaws, did rescue the economy), but the CHIPS and Science Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and the Inflation Reduction Act, the latter of which came out of the Build Back Better negotiations outlined above.

This is all true. I suspect the infrastructure and CHIPS bills would have come together under any president, but Biden did sign them. The problem is he failed to run an administration that prioritized effectively implementing the laws he did pass.

As in his legislative strategy, Biden’s executive strategy was motivated by a desire to serve several different ends: fighting climate change, fighting China, rebuilding US manufacturing, helping unions, and so on. This often meant that spending approved by Congress came with so many strings attached as to be practically unusable. Other spending was hobbled by administration actions making the products being subsidized unnecessarily more expensive.

Why, after fighting so hard for the CHIPS and Science Act, did the administration lard on so many requirements for manufacturers to meet, from a “climate and environment responsibility plan” to a National Environmental Policy Act analysis to a plan to include small businesses with women or minority owners in the supply chain, all of which has hobbled implementation?

Why, given his climate goals, is Biden imposing tariffs on solar panels — and not just ones from China — that effectively raise the price of clean energy, and limit the Inflation Reduction Act’s effectiveness?

Why was the $42 billion in broadband internet funding in the bipartisan infrastructure law so hard to access that, as of this writing, exactly 0 people have gotten broadband as a result of that money?

Like any president, Biden had to optimize toward many different goals in his domestic policy. But he never seemed to have a clear sense of which of these goals were most important, and what should win out when they conflicted with each other. It was an indecision that plagued his legislative prioritization, too.

It perhaps should not surprise us too much that Biden failed to craft a coherent domestic agenda. In a telling slip-up shortly before Obama’s inauguration in 2009, Jill Biden told Oprah Winfrey that Obama had offered her husband a choice: vice president, or secretary of state. (Biden himself has told a variant of this story, too.)

The secretary of state job in some ways seemed more plausible. Biden’s own primary campaign had ended after getting fifth place in Iowa, with 0.9 percent to Obama’s winning 37.6. But he was the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and had years of foreign policy experience. He was widely seen as a frontrunner for secretary of state had John Kerry won in 2004. Jill Biden stated that her husband chose VP because it meant less travel and more time at home with his family.

The flip side to this passion was a relative disinterest in domestic affairs. Not a total disinterest, of course — Biden used to chair the Senate Judiciary Committee, wrote important (and controversial) criminal justice legislation, and was deeply invested in his identity as a guy who cared about regular, middle-class folk. But he never demonstrated much concern with or interest in the details of domestic policy in the way he did with foreign policy. Biden’s willingness to let Schumer turn the American Rescue Plan into a wish list for his most progressive members reflected, in part, a Biden that didn’t especially care about the contents of that wish list.

Another, perhaps underrated factor constraining Biden was the nature of his 2020 primary win.

It is easy to forget now, but Biden’s victory came almost out of nowhere. More than his victory in South Carolina, it was the choice of fellow candidates Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar to drop out and endorse him, and the behind-the-scenes help of key party figures like Obama, that let him consolidate support after that primary and defeat Bernie Sanders in the ensuing contests.

Biden less won than he was given the nomination by party leaders eager to head off a Sanders nomination, and the party’s voters supported that decision. That did not give him much of the authority that a nominee typically commands. Obama and Clinton won their nominations because they were once-in-a-generation political talents with supporters eager to back them up; Biden won, after two failed presidential campaigns beforehand, because the party was desperate to beat Trump and needed a moderate, any moderate.

He came out of that process owing a lot of people a lot of favors. But even though it was perceived moderation that had largely gotten him the nomination, he also left the primary feeling a strong need to patch things up with the Sanders wing and avoid a party split ahead of the general election. That led to an unusual decision to swing leftward in the general. His team set up “unity” task forces with Sanders allies, hashing out a policy agenda that promised bigger spending and more ambitious regulatory efforts than supported by Biden’s primary campaign. Once in office, he filled his administration with Elizabeth Warren loyalists, a reflection both of Warren’s skill at personnel promotion and Biden’s feeling that he needed to pacify his left flank.

This attitudinal shift is palpable when you read accounts from journalists like Foer, Martin, and Burns about the 2021–2022 period. Complaints from Congressional Progressive Caucus members like Pramila Jayapal are given prominence over the desires of Manchin and Sinema — even though House backbenchers had zero leverage over Biden’s agenda. They could not credibly threaten to vote against Build Back Better legislation, the way Manchin and Sinema could and did. If they did, the bill would fail, leaving the country with no progress toward progressives’ shared goals, or become more right-wing to win more moderate votes.

The best gambit the Progressive Caucus had was a threat to vote against an infrastructure bill that Manchin wanted, but the gambit failed. Even if they had held the line, the likely outcome would have been neither an infrastructure bill nor a Build Back Better. It was all pointless theater.

But the White House was deeply sympathetic to the goals of the House progressives, and so you got bizarre spectacles like Biden visiting the Hill ostensibly to whip votes for the infrastructure bill at Nancy Pelosi’s request, only for him to never explicitly ask progressives for their votes, and instead seem to endorse their strategy. “When Pelosi thought about the White House, she struggled to understand Biden’s behavior,” Foer writes. “He flat-out whiffed. Why wasn’t Biden pressing harder for victory? Why was he so afraid to demand the loyalty of his party in his time of need?”

This was not the behavior of a president who confidently defeated Warren and Sanders, but of a president who felt he could not offend their factions of the party no matter what. It was the behavior of a president who could not choose.

Just how much Biden was involved in presidential-level decision-making at all is, of course, a fraught question now. Since last June’s debate with Trump, revelations have mounted showing that Biden was much more cognitively compromised, and his staff much more active in concealing this fact from the American people, than I at least had previously believed.

A December article in the Wall Street Journal reported that Biden’s diminishment meant that senior advisers like national security adviser Jake Sullivan, counselor Steve Ricchetti, and National Economic Council head Lael Brainard were making decisions that normally the president makes. Worse, the report shared that, “Press aides who compiled packages of news clips for Biden were told by senior staff to exclude negative stories about the president.”

Obviously, a Biden who was making fewer and fewer decisions himself, and increasingly insulated from any negative potential information that could result in productive changes in policy, is going to prove ineffectual.

The obvious Shakespearean reference for Biden is Lear, an aging and vain king who is losing his wits and is tormented by his children. But ultimately his downfall was more Hamlet. Biden led America at a pivotal moment that called for strong decisions. He just could not make them.

Recent Comments