If we are, as some city officials have said, in a war with rats, we are clearly losing. We’ve been losing for years.

Although cities have ramped up their use of poisons and traps, the number of rats in places like New York City, San Francisco, and Toronto has increased in recent years, according to a new study published in the journal Science Advances. The researchers analyzed rat complaints and inspection reports for 16 cities that had consistent, long-term data available. More than two-thirds of those cities saw a significant increase in rat sightings.

Washington, DC, had the largest increase in sightings over roughly the last decade, according to the study, which is the most comprehensive assessment of city rats to date.

“We are on our heels and being pushed backward,” Jonathan Richardson, the study’s lead author and an ecologist at the University of Richmond, said about the fight against rat infestations.

There’s more bad news: The study found a strong link between an increase in rats and rising temperatures, a consequence of climate change. Cities that warmed more quickly had larger increases in rat sightings, the research found. This is in part because, with warmer winters, rats can spend more time eating and reproducing and less time hunkering down underground.

Scientists project that urban areas will warm by between 3.4 and nearly 7.9 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century, depending on how much oil and gas we burn. Cities tend to be hotter than rural areas — because concrete and other human infrastructure absorb and re-emit more heat than vegetation — and warm faster. That means that not only are current rat control methods failing, but the problem is likely to get much worse.

It’s a good thing, then, that there’s an obvious solution. And better yet, it’s simple.

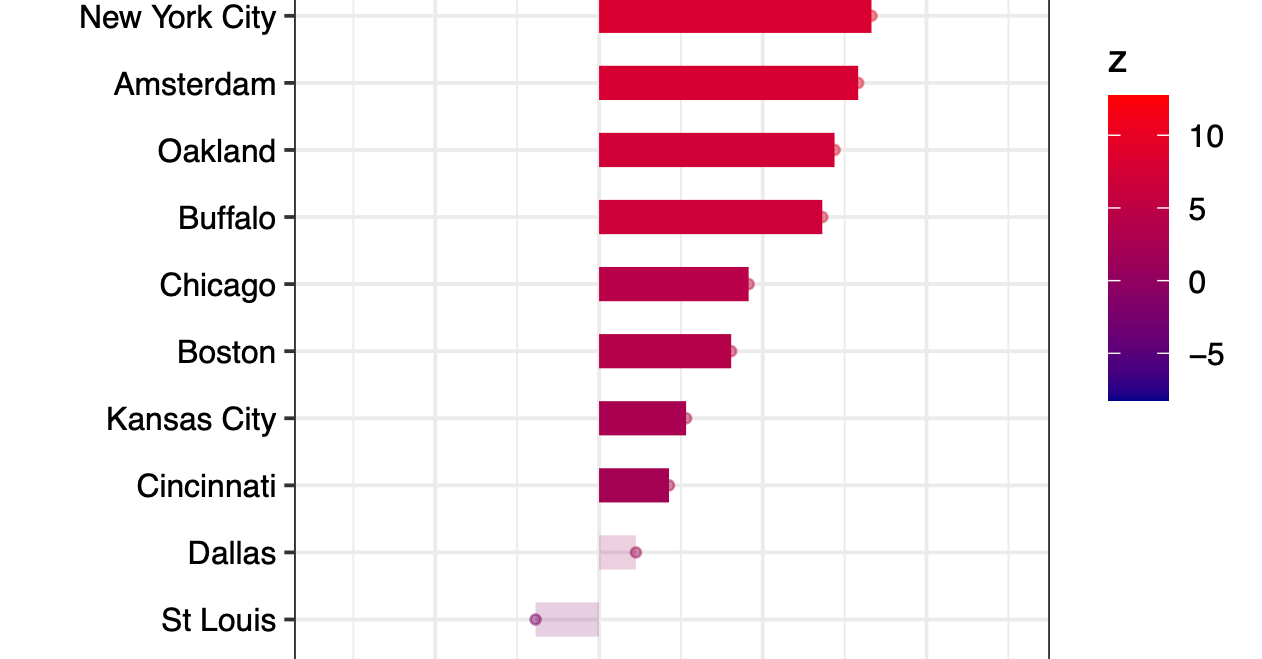

The cities where rat sightings are growing the fastest

While rats are easily the most common urban mammal, cities don’t actually know how many of them there are. They don’t run a census for rats like they do for, say, squirrels. So to figure out how their populations are changing, researchers rely instead on proxies, such as 311 complaints — when disgruntled tenants or parkgoers or diners report an infestation to city officials. Those complaints have been shown to correlate with the abundance of rats, though they’re imperfect approximations. Plenty of factors, beyond the sheer number of rats, influence whether or not someone complains, including their relationship with their landlord and trust in the city government.

The new study relies on those public complaints, though it also uses inspection reports, which are created by city officials who inspect a property for rats, either following a complaint or as part of a proactive sweep. The authors identified 16 cities, most of which are in the US, that reported this data consistently for at least seven years.

The figure below shows how rat sightings in those cities have changed. Cities with red bars show an increase in rat sightings; longer bars show greater increases. Blue bars, in contrast, indicate rat sightings have decreased. The takeaway is that DC, San Francisco, Toronto, and New York City have seen a surge in sightings over the last several years, whereas rat sightings in New Orleans and Tokyo have dropped.

The researchers also explored what might be driving those trends, and ultimately linked rat sightings with temperature, the degree of urbanization (i.e., a lack of green space), and human population density.

None of this is particularly surprising. When it’s cold, rats and other small mammals burrow underground to stay warm. “This is called vertical migration,” said Michael Parsons, an urban ecologist and rat expert. “They just keep going deeper and deeper the colder it gets. As that’s occurring, they’re not mating.”

They’re not eating as much, either, said Parsons, founder of the consulting firm Centre for Urban Ecological Solutions. Food doesn’t smell as much when temperatures drop, making it harder for rats — who rely on their nose for foraging — to find their next meal. (As a cute but also gross aside, rats apparently smell each other’s breath to determine what foods they like.)

Taken together, this means that as cities warm, rats have more time to eat and mate, and they can more easily locate food. This could help explain why New Orleans didn’t see an increase in rats, Parsons said. The city already has a warm, subtropical climate, so additional warming may provide less of a benefit for its rats. Too much heat could eventually become a problem, Richardson said, but rodents seem to be less limited by heat than by cold.

“For millennia — for decades, centuries in New York City — we’ve relied some on winter cold snaps to support population controls,” said Kathleen Corradi, NYC’s director of rodent mitigation, also known as the rat czar. “We continuously have warmer winters. We know the impact that has on these populations.”

Meanwhile, cities with less green space (meaning more buildings and more urbanization) and higher densities of people saw larger increases in rats, the study found. That’s likely because human infrastructure, such as homes and restaurants, are a more constant source of food, compared to big parks. This is concerning because urban land and human populations living in cities are expected to grow in the coming years.

Basically, the future is shaping up to be a lot rattier.

Why are humans so bad at controlling rats?

More rats, in short, is not great. These animals can carry dozens of pathogens and parasites, such as the bugs that cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, a severe lung disease, and, you know, bubonic plague.

There’s also a growing body of research that links rat infestations to mental illnesses including depression and psychological trauma. A recent study in Chicago found that people who saw rats in their homes daily or almost daily were five times more likely to report serious symptoms of depression. And poor neighborhoods tend to face the brunt of these problems because they often harbor more rats.

This is to say: There are some very important reasons to reduce rat populations.

Yet despite decades of anti-rat efforts costing hundreds of millions of dollars, infestations in many big cities are only getting worse. In some cases, much worse. Why haven’t we — humans, with human-sized brains and human technology — done a better job at controlling these animals?

Part of the problem, experts told Vox, is that for much of the last century, cities have relied on rodenticides and baited traps to eradicate rats.

This approach just doesn’t work.

“It’s fairly clear that widespread application of rodenticide does not curb rat populations,” said Jason Munshi-South, an ecologist and rat expert at Drexel University. “What it does is kill rats on a local level, so it feels like you’re doing something. But you’re up against the brutal math of rodent reproduction.”

A well-fed mother rat can have 10 or more babies in a litter, and have several litters a year. Plus, poison doesn’t reach every rat, and some have learned to avoid it.

What poison does do is cause gnarly deaths for rats — often leading to prolonged internal bleeding — and it kills other wildlife, too. When scientists collect dead birds of prey, they find rodenticide in most of them. “Dying from rodenticide like an anticoagulant is a terrible way to die,” Munshi-South said.

Exterminators continue to rely heavily on poison and baits in part because it’s easy, Richardson said. “They’re just doing what they have the capacity to do in a practical, short time frame,” he said.

The status quo is also benefitting the extermination industry.

“Exterminators don’t get paid to remove rodents entirely,” Parsons said. “They get paid to control rodents so that they’re always needed. I’m not at all cynical. This is just the way it works.”

Here’s what actually works

There’s only one way to actually get rid of rats: Get trash off the street. That’s literally it.

“It’s not rocket science,” Richardson said. “We know what we have to do.”

Controlling rats requires putting trash in sturdy bins with tops that rats can’t easily chew threw, and not in bags on the curb. It requires that people don’t litter. It requires cleaning up.

Again, not complicated.

Trying to tweak enormous, citywide systems and behavior norms, however, is a challenge. Cities or building owners may have to buy new bins and maintain them. Trash collectors may need to tweak their operations and use new trucks. Residents may need to be educated on proper disposal. Parking spots may need to be removed to make space for large waste bins. Multiple city agencies may need to get involved, including health, sanitation, and housing departments. “It’s not as easy as it sounds,” Munshi-South said.

But this approach clearly works. New York, arguably the most famous ratty city (with its very own rat celebrities), recently required that most city trash be placed in containers with secure lids, not in plastic bags on the street. Progress! And preliminary data suggests these changes may have already put a dent in rat complaints, Richardson said.

Under Mayor Eric Adams’s administration, so-called containerization is “the hallmark” of the city’s battle with rats, Corradi told Vox. “We’re so optimistic and excited to see that rollout and its impact on rats, because food source is what has allowed rats to thrive for so long in New York City and other urban centers,” she said.

Tokyo’s decline in rat sightings likely also has to do with containing food waste. The city’s culture puts a lot of value on sanitation, Richardson said. Restaurants and other businesses get shamed if people spot rats nearby, he said, and the growth of social media has made shaming easier. Japan has also deployed other anti-rat approaches including infusing garbage bags with the smell of herbs.

There’s a similar story in New Orleans, which saw an even steeper decline in sightings: The city has put a lot of work into educating residents and government agencies about behaviors that support rats, such as leaving out trash and debris, Richardson said.

Ultimately, Corradi said, what makes fixing rat infestations so hard is that “rat issues are human issues.” It’s human behavior that allows rats to thrive in the first place.

Put another way, the rats aren’t to blame, Parsons said.

“Rats would still be in northern Mongolia hanging out in their burrows if it weren’t for these food crumbs that were dropped all the way across the continents,“ he said. “It’s just so much easier for us to kill another species and bludgeon it to death — in some cases, torture it — than it is for us to just pick up after ourselves.”

Rats are affectionate, Parsons said. They laugh. They’re empathetic, in some cases, giving up chocolate to save a drowning companion.

“There’s just enough [research] out there that we need to stop being barbaric in our approach to animals,” he said. “They deserve to have basic welfare.”

Recent Comments