Earlier this month, Thomas Edsall published a column in the New York Times titled, “Even if the Democrats can move to the center, it may not help.” In it, the eminent political analyst argued that “there is evidence that the process of moderation has the potential to result in unintended adverse consequences.”

Edsall was referring to a new working paper from Stanford University political scientist Adam Bonica and two co-authors. As Bonica explained in an interview with the Times, his research points toward “a clear conclusion: There appears to be very little electoral advantage from running to the center in contemporary congressional elections.”

According to Bonica, although moderate candidates were a little better at persuading voters to support them, this advantage was tiny and potentially outweighed by moderation’s negative impact on turnout.

“Democrats have achieved their greatest electoral successes precisely in cycles (2008 and 2018) when they did not moderate relative to Republicans,” Bonica told the Times, while “in cycles where Democrats ran more moderate candidates (like 2010 and 2014), their electoral performance was notably weaker.” He also reiterated these claims in a viral Bluesky thread.

This story was first featured in The Rebuild.

Sign up here for more stories on the lessons liberals should take away from their election defeat — and a closer look at where they should go next. From senior correspondent Eric Levitz.

All this has triggered a lively debate about how Democrats should weigh Bonica’s evidence against the many studies showing that moderation is electorally beneficial on net. The election analysis site SplitTicket noted that Bonica’s “finding cuts against everything we’ve modeled.”

But this debate proceeds from a false premise: Bonica’s data doesn’t actually cut against the idea that moderation is beneficial.

On the contrary, his study indicates that moderation can significantly increase Democrats’ support with swing voters, especially in high-profile races. He and his co-authors note it is theoretically possible that this benefit is outweighed by moderation’s negative impact on Democratic turnout. But, by their own admission, they possess no strong evidence that such a negative impact exists.

Judging by Bonica’s data, a conservative Democrat probably would have beaten Donald Trump in 2016

The bulk of Bonica’s paper aims to calculate how candidates’ ideological positioning impacts their electoral performance. The study argues that previous attempts to gauge this relationship have been distorted by a failure to control for voter turnout. As the authors note, a “candidate’s ability to shift overall turnout is limited,” since voter participation is influenced by many factors external to their campaigns. For example, if a state has a high-profile abortion referendum on the ballot, then Democratic candidates in that state could enjoy elevated base turnout, even if their own stances did little to mobilize voters. Meanwhile, Democrats in a state with no such referenda might see lower turnout through no fault of their own.

To account for this, Bonica and his co-authors look at how ideologically distinct candidates — on the ballot at the same time — performed within the same precincts.

Specifically, for each race on the ballot, they calculate the “ideological midpoint” — basically, the point on a left-to-right axis that is halfway between the Democratic and Republican candidates’ respective ideological position — and then measure how vote-share changes as this midpoint shifts rightward or leftward.

The idea here is: When the midpoint lies to the right, the Republican candidate is more conservative than the Democratic candidate is progressive. When the midpoint lies to the left, the opposite is true.

They find that the farther right this midpoint moves in a given race, the better Democrats do. Now, on its face, this could just mean that Democrats do better when they run against far-right Republicans — the more conservative the GOP candidate in a race is, the farther right the midpoint will be, no matter the ideology of their Democratic opponent. But the study shows that it doesn’t really matter why the ideological midpoint shifts right: Democrats becoming more moderate increases the party’s vote share by about as much as Republican candidates becoming more conservative.

From this, they extrapolate that, on average, centrist Democrats (e.g., Sen. Joe Manchin types) enjoy a roughly 0.6 percentage point advantage over mainstream ones (e.g., Sen. Amy Klobuchar types) across all races, when turnout is held constant.

The Times presented this tiny fraction as evidence that moderation’s benefits might be negligible. And yet, according to Bonica’s study, the impact of ideology on electoral outcomes varies widely by office: In high-profile races — where voters are more likely to receive information about the candidates’ positions — centrists enjoy a bigger advantage over their more left-wing counterparts. In governors’ races, the former outperform the latter by 1.9 percentage points; in presidential and Senate races, they outperform by about 1 point. These are not insignificant margins: Had Hillary Clinton’s share of the vote been 1 point higher in 2016, she likely would have won the presidency.

By contrast, ideology has almost no impact on state-level races for judicial positions and other minor state-level offices, likely because voters do not pay close attention to candidates’ positions in such races. The negligible impact of ideology in these low-profile races drags down the average benefit of moderation in the paper. That said, moderates’ advantage in House races specifically is barely higher than their average advantage across all offices, at just 0.65 points.

Importantly, all of these figures are measuring conservative Democrats’ advantage over mainstream Democrats. The study implies that the performance gap between conservative Democrats and progressive Democrats would be larger.

Bonica’s paper provides little evidence that moderation is bad for turnout

Bonica’s case for questioning moderation’s efficacy hinges on a speculative premise: that centrism might do more to demobilize base voters than to persuade swing voters. But his paper does not even attempt to prove this.

The study does provide evidence for two claims about the relationship between turnout, ideology, and election outcomes:

• When turnout among Democrats goes up — relative to turnout among Republicans — Democrats win more elections. And the benefits of turning out a higher percentage of your voters than the other party did are quite large — far larger than the benefits of moderation.

• Between 2008 and 2022, Democrats tended to see stronger turnout — and better outcomes — when the average ideological midpoint of all House races was more left-wing.

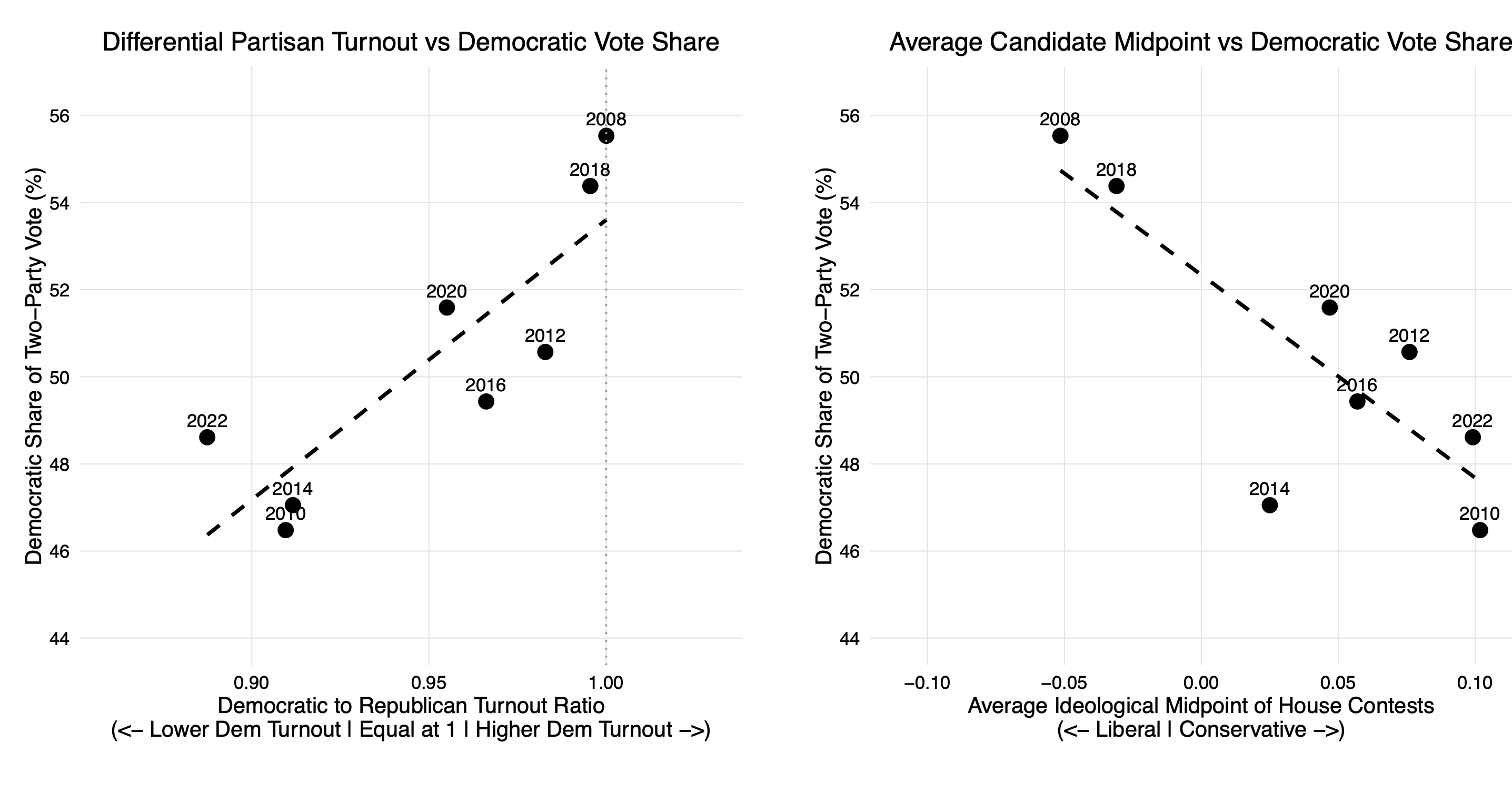

They illustrate these two points with a pair of charts:

But I think the evidence here is weaker than Bonica’s Bluesky posts — or Edsall’s write-up in the Times — would lead one to believe.

For one thing, we are looking at only eight data points — the eight federal election cycles from 2008 through 2022. And not all eight conform to Bonica’s trend lines.

Within his data set, Democrats suffered their second-worst election loss and turnout showing in 2014. And yet, the ideological midpoint that year was unusually left-wing (only in 2008 and 2018 did the ideological midpoint of House races lie farther to the left).

In 2016, meanwhile, the ideological midpoint of all House races was more left-wing than it had been in 2012. And yet Democrats saw better turnout during the earlier election cycle.

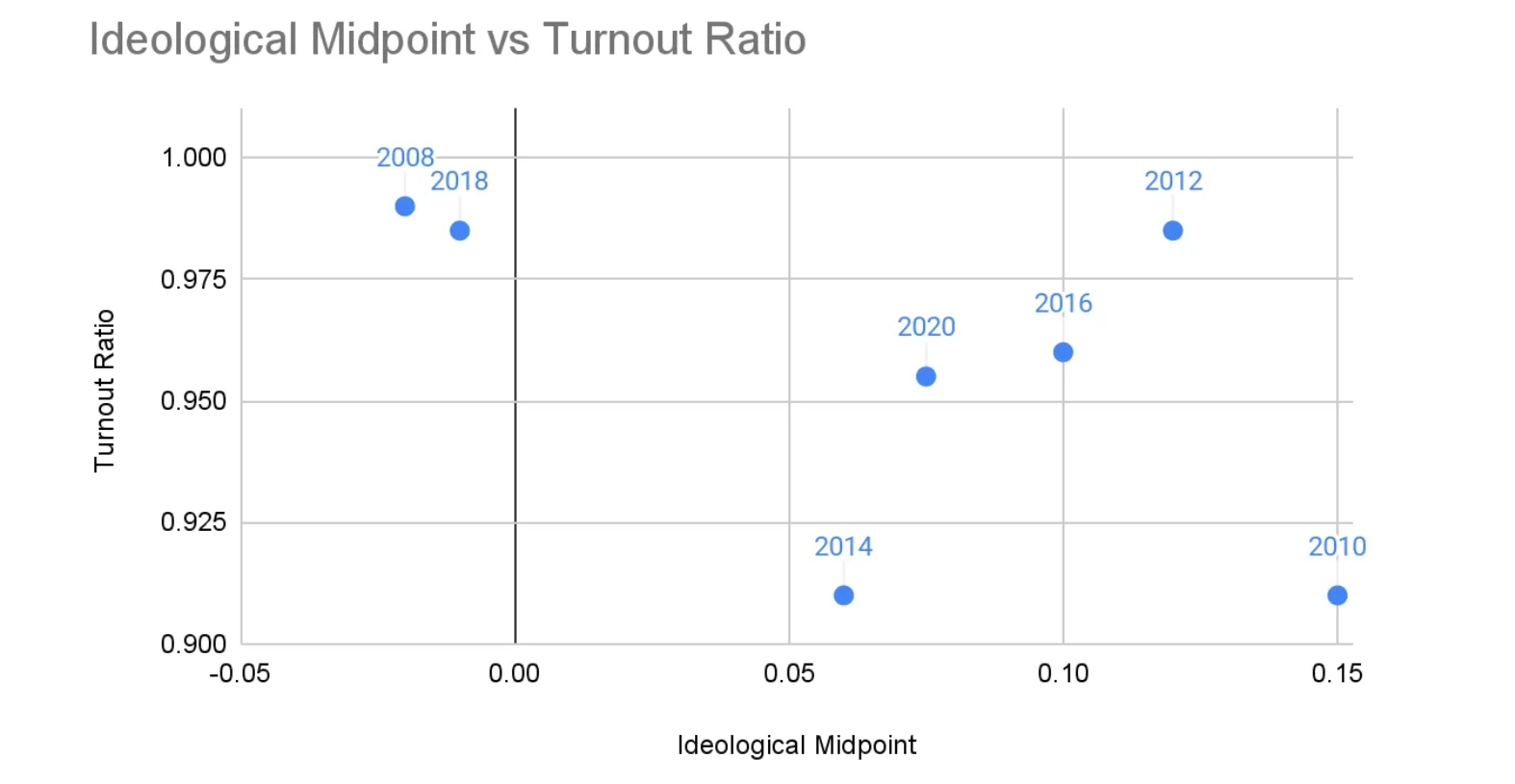

Indeed, it’s not clear that there is any relationship between ideological positioning and turnout in Bonica’s data. When the Democratic pollster Charlotte Swasey tried to chart out this relationship, using Bonica’s findings for the years 2008 through 2020, she found no clear trend:

And Bonica’s proposed correlation breaks down even further when one looks directly at changes in Democratic ideology. Remember: Shifts in the ideological midpoint are influenced by both Republican and Democratic positioning. So to isolate the impact of Democratic moderation on turnout, we should really look at how the average Democratic candidate’s ideology changes from year to year, rather than at how the ideological midpoint changes.

Such figures aren’t reported in Bonica’s paper. But he provided me with the relevant numbers. And several of them cut against the idea that moderation leads to lower turnout:

• Democrats were more moderate in 2008 than in 2014, yet the party saw much better turnout in the former year.

• Democrats were more moderate in 2018 than in 2020, yet the party saw better turnout (relative to the GOP) in 2018.

• Democratic candidates were more moderate in 2012 than in 2016, yet the party had better turnout in 2012.

• Democratic candidates were more moderate in 2018 than in 2022, yet saw better turnout in 2018.

• Democratic candidates were more moderate in 2016 than in 2020, and yet — according to Bonica’s data — the party actually had slightly better turnout (relative to Republicans) the year that Hillary Clinton lost than in the year that Biden won.

In short, Bonica’s numbers don’t actually show that moderation even systematically correlates with worse Democratic turnout, much less that the former causes the latter. Rather, his data suggests that the Democratic Party has grown increasingly progressive since 2008, and that this leftward drift has had no predictable impact on Democratic turnout from year to year.

And there are simpler explanations for why Democrats saw strong turnout in 2008 and 2018, but weak turnout in 2010, 2014, and 2022.

In 2008, Democrats ran an extraordinarily charismatic, historically significant presidential candidate against a GOP that was presiding over a financial crisis.

Meanwhile, the party that doesn’t hold the presidency almost always has an advantage in midterm elections, in part because their opposition’s base grows complacent with power. This dynamic explains why Democrats saw relatively high turnout in 2018 (when a Republican held the White House) but relatively weak turnout in 2010, 2014, and 2022 (when a Democrat held the presidency).

In an interview, Bonica told me that he has “tried to make clear” that his proposed trade-off between moderation and turnout is a “potential” one that “hasn’t been causally established.”

“What we do learn from the paper is that the overall gains from moderation are just quite small,” Bonica said.

Nevertheless, his findings offer more cause for thinking that moderation increases Democratic vote-share than for thinking that it reduces the party’s turnout.

And other research gives us reasons to doubt the latter premise. According to many political scientists and pollsters, very liberal Democrats are the party’s most reliable voters. It is Democrats with more moderate — or heterodox — views who waffle the most about whether to cast a ballot. And these less politically engaged Democrats often resemble swing voters ideologically and demographically. For this reason, the forces that push swing voters to the right — and those that nudge unreliable Democratic voters toward staying home — are sometimes one and the same.

Progressives should not jump to ideologically convenient conclusions on the basis of weak evidence

It doesn’t necessarily follow that Democrats should move to the right. There are strong substantive arguments for many progressive policies. And the political benefits of moderation in Bonica’s paper aren’t terribly large.

Regardless, it’s more productive to debate how the party should position itself on discrete issues than whether it should “move right” or “move left.” Some policies associated with the left are popular, some associated with the center are not. So, it’s helpful to get specific.

Nevertheless, it’s important to be clear-eyed when analyzing the relationship between ideological positioning and electoral outcomes. In progressive circles, empirical claims about the efficacy of moderation are often imbued with moral weight: To say that Democrats would benefit from moderating on any issue is to betray vulnerable minority groups, while denying the efficacy of moderation is to defend those groups.

But this is misguided. Refusing to consider ideologically inconvenient data makes it harder to win elections. And as the current administration is making clear, the most vulnerable have a strong interest in Democrats winning elections. According to some estimates, Donald Trump’s defunding of USAID alone has cost more than 10,000 human beings their lives. The election of literally any Democrat last November would have averted those deaths. On a wide variety of fronts, a Joe Manchin presidency would have meant less needless cruelty and suffering than a Trump one. If there is evidence that a Manchin-esque Democrat would have done better than Kamala Harris, we have a responsibility to take that information into account.

People will inevitably disagree about how Democrats should balance policy idealism with political expediency. But any rational answer to that question must be premised on an accurate understanding of the relevant tradeoffs. Bonica’s research could help advance such an understanding. But the discourse around it has done the opposite.

Recent Comments