Democrats have spent months debating how and why they lost the 2024 election. But the full picture of what happened on Election Day is only now coming into view.

The most authoritative election analyses draw on a variety of different data sources, including large sample polling, precinct-level returns, and voter file data that shows definitively who did and did not vote. And those last figures became available only recently.

The Democratic firm Blue Rose Research recently synthesized such data into a unified account of Kamala Harris’s defeat. Its analysis will command a lot of attention. Few pollsters boast a larger data set than Blue Rose — the company conducted 26 million voter interviews in 2024. And the firm’s leader, David Shor, might be the most influential data scientist in the Democratic Party.

I spoke with Shor about his autopsy of the Harris campaign. We discussed the problems with the popular theory that Democrats lost because of low turnout; why zoomers are more right-wing than millennials; how TikTok makes voters more Republican; where Donald Trump’s administration is most vulnerable; what Democrats can do to win back working-class voters; and whether artificial intelligence is poised to turbo-charge America’s culture wars, among other things. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and concision.

Key takeaways

• Democrats lost the most ground with politically disengaged voters, immigrants, and young people.

• If every registered voter had turned out, Democrats would have lost by more.

• TikTok appears to make its users more Republican.

• Nonwhite moderates and conservatives are voting more like their white counterparts.

• The gender gap among young voters was historically massive in 2024.

• Democrats lost voters’ trust on the economy and cost-of-living.

• Democrats’ most effective message in 2024 was an economically populist one.

• Donald Trump is leaning into the most unpopular parts of his agenda.

• Democratic constituencies are much more vulnerable than Republican ones to AI-induced unemployment.

Before we get into why Democrats lost the 2024 election, let’s talk about how they lost it: Which voting blocs shiftest the furthest right over the past four years?

The most important thing is that we saw incredible polarization on political engagement itself. There’s a bunch of different ways to measure this: There’s how many elections you vote in, or how important politics is to your identity. There’s how closely you follow the news. But across all of these, there’s a consistent story: The most engaged people swung toward Democrats between 2020 and 2024, despite the fact that Democrats did worse overall.

Meanwhile, people who are the least politically engaged swung enormously against Democrats. They’re a group that Biden either narrowly won or narrowly lost four years ago. But this time, they voted for Trump by double digits.

And I think this is just analytically important. People have a lot of complaints about how the mainstream media covered things. But I think it’s important to note that the people who watch the news the most actually became more Democratic. And the problem was basically this large group of people who really don’t follow the news at all becoming more conservative.

If they’re not responding to mainstream media information, where are they getting their views on politics? Is this group reacting to the prices at the grocery store, or firsthand experience of changes in the economy, immigration, or culture?

Most people have to balance their reaction to objective facts in the economy with their preexisting ideological beliefs. A strongly Democratic voter isn’t going to switch to Trump just because they’re upset about high prices. So, it isn’t too surprising that the people with the weakest political loyalties would be the most responsive to changes in economic conditions.

And people who are politically disengaged — like every other subgroup of people this election — overwhelmingly listed the cost of living as the thing they were the most concerned about.

But it can’t just be inflation. Politically disengaged voters went from being a roughly neutral group in 2020 to favoring the Republicans by about 15 points in 2024. But during the Obama era, this was a solidly Democratic group, favoring us by between 10 and 15 points. So there’s also this long-term trend that goes beyond inflation or social media. Our coalition has been transitioning from working-class people to college-educated people.

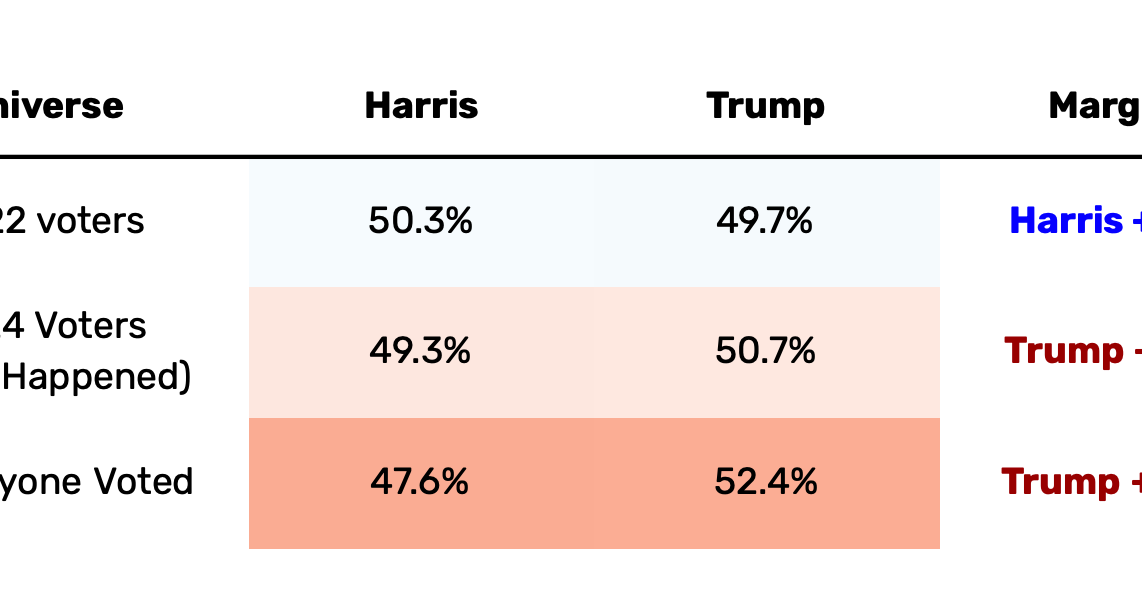

To move beyond the why, this shift in the partisanship of politically disengaged voters has a really important implication: For most of the last 15 years, we’ve really lived in this world where the mantra was “If everybody votes, we win.” But we’re now at a point where the more people vote, the better Republicans do.

If I understand you correctly, you’re suggesting that Democrats cannot rebuild a national majority merely by juicing higher turnout, since registered voters as a whole were more pro-Trump in 2024 than those who actually showed up at the polls.

Nevertheless, many progressives have attributed Harris’s loss to depressed turnout among Democratic voters specifically. They point to the fact that, between 2020 and 2024, the Democratic presidential nominee’s vote total fell by significantly more than Trump’s tally increased. And they also note that, according to AP Votecast, only 4 percent of Biden 2020 voters backed Trump last year — while a roughly equal percentage of Trump 2020 voters switched to Kamala. So, in their telling, if defections roughly canceled out while a large number of voters went from supporting Biden to staying home, then clearly the problem was inadequate Democratic turnout. So if Harris had focused more on energizing the progressive base, she might have won. What do you think is wrong with that narrative?

Well, the problem with the AP VoteCast data is that it was released the day after the election. There was just a lot of information that they didn’t have at the time. At this point, voter file data has been released for enough states to account for an overwhelming majority of the 2024 vote. And what’s really cool about having that data is that you can really decompose what fraction of the change in vote share was people changing their mind versus changes in who voted.

And when you do that, you see that roughly 30 percent of the change in Democratic vote share from 2020 to 2024 was changes in who voted — changes in turnout. But the other 70 percent was people changing their mind. And that’s in line with the breakdown we’ve seen for most elections in the past 30 years.

The reality is that these things always tend to move in the same direction — parties that lose ground with swing voters tend to simultaneously see worse turnout. And for a simple reason. There were a lot of Democratic voters who were angry at their party last year. And they were mostly moderate and conservative Democrats angry about the cost of living and other issues. And even though they couldn’t bring themselves to vote for a Republican, a lot of them stayed home. But basically, their complaints were very similar to those of Biden voters who flipped to Trump.

The reality is if all registered voters had turned out, then Donald Trump would’ve won the popular vote by 5 points [instead of 1.7 points]. So, I think that a “we need to turn up the temperature and mobilize everyone” strategy would’ve made things worse.

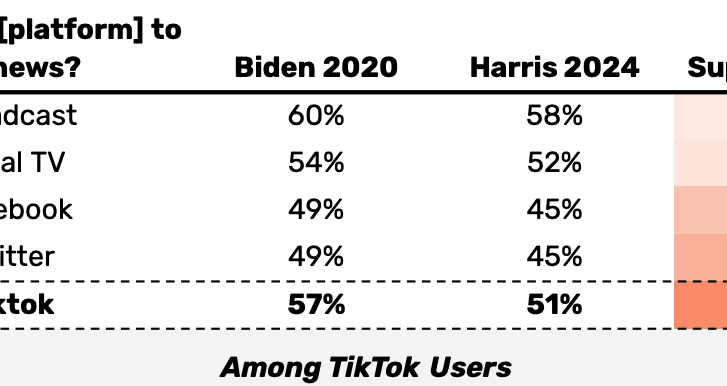

According to your data, voters who got their news from TikTok were much more likely to swing to the GOP than other voters, even after controlling for demographics. Why do you think that is?

I think people can debate how much of this is the nature of the algorithm versus the strategic choices that the parties made. A lot of people argue that maybe TikTok just helps negative content get promoted, and that’s naturally bad for whoever’s the incumbent. But TikTok is also really different from social media that came before.

Other social media sites are very dependent on what people call “the follower graph.” If you look on Instagram Reels, for example, the correlation between how many views a video gets and how many followers the creator has is extremely high. On TikTok, it’s quite a bit lower than any other platform. And the reason is TikTok uses machine learning to analyze a video — and make a good guess about whether it will be appealing — before they show it to anyone. So if your video is likely to be engaging, it can get wide distribution even if you don’t have a following. And that has been genuinely democratizing.

We used to live in this world where in order to get your message out there, you had to get people who write really well to absorb your message and put it out. And now, we’re in a world where anyone can make a video and if that video is appealing, it’ll get out there. And this is naturally bad for the left, simply because the people who write really well are a lot more left-wing than the overall population.

One of my favorite stats on this is something that Nate Cohn put out a couple years ago: Working-class white voters who’ve read a book in the last year are much more Democratic than working-class white voters who haven’t.

So what other groups did Democrats lose ground with, beyond those who pay little attention to politics and TikTok enthusiasts?

If you look at predominantly immigrant neighborhoods, whether they’re white or Hispanic or Asian or African, you really see these absolutely massive shifts against Democrats. Trump won Corona in Queens. Immigrants go from a D+27 group in 2020 to a potentially R+1 group in 2024.

I’m not sure why that happened. I think we’re still waiting for data to come back. But I’d guess it’s the same stories about the cost of living and cultural issues and ideological polarization.

Speaking of ideological polarization: One of the findings in your data is that nonwhite voters who identify as “conservative” or “moderate” have been voting more and more like their white ideological counterparts over the past few elections. So, the electorate is polarizing less on race and more on ideology.

I feel like there’s an argument that this was inevitable: Hispanic and Asian Americans were always likely to follow the political trajectory of other immigrant groups, many of which were tethered to the Democratic Party for the first couple of generations but then started to polarize ideologically as they became more affluent and assimilated. And you could perhaps tell a similar story about Black Americans, in which the easing of extreme racial oppression and segregation makes it easier for conservative African Americans to consider voting for the GOP.

On the other hand, maybe Democrats just made some avoidable mistakes that alienated these constituencies. So I’m wondering how you understand this development?

If we look at 2016 to 2024 trends by race and ideology, you see this clear story where white voters really did not shift at all. Kamala Harris did exactly as well as Hillary Clinton did among white conservatives, white liberals, white moderates.

But if you look among Hispanic and Asian voters, you see these enormous double-digit declines. To highlight one example: In 2016, Democrats got 81 percent of Hispanic moderates. Fast-forward to 2024, Democrats got only 57 percent of Hispanic moderates, which is really very similar to the 51 percent that Harris got among white moderates.

You know, white people only really started to polarize heavily on ideology in the 1990s. Now, nonwhite voters are starting to polarize on ideology the same way that white voters did.

If you look at African Americans, they did not swing nearly as much. But in our polling, before the Kamala switchover, Black voters were poised to swing 7 to 8 percentage points against us.

As to whether this is inevitable, I would say that to some degree getting 94 percent of any ethnic group is unsustainable. But I think that the losses that we’re seeing among nonwhite voters and immigrants is symptomatic of this broader, ideological polarization that Democrats are suffering from.

Fundamentally, 40 percent of the country identifies as conservative. Roughly 40 percent is moderate, 20 percent is liberal, though it depends exactly how you ask it. Sometimes it’s 25 percent liberal. But the reality is that, to the extent that Democrats try to polarize the electorate on self-described ideology, this is just something that plays into the hands of Republicans.

This isn’t necessarily as ideologically restrictive as people think. If you look at moderates — and especially nonwhite moderates — a bunch of them hold very progressive views on a variety of economic and social issues. A very large fraction of Trump voters identify as pro-choice. We’ve seen populist economic messaging do very well in our testing with voters of all kinds. But I think that there are also some big cultural divides between highly educated people who live in cities and everybody else. And to the extent that we make the cultural signifiers of these highly educated people the face and the brand of our party, that is going to make everyone else turn against us.

One surprising thing

Young people have been one of the most reliably Democratic constituencies for more than a decade. According to the Democratic data firm Catalist, Joe Biden won voters under 30 by 23 points in 2020. But Blue Rose Research’s data suggests that Trump narrowly won that demographic in 2024.

How do young voters fit into this? In my understanding, young voters shifted significantly against Democrats in 2024.

Yeah. So this is related to the other trends: Young people are more nonwhite than the overall electorate. They’re more politically disengaged than the overall electorate. But the single biggest predictor of swing from 2020 to 2024 is age. Voters under 30 supported Biden by large margins. But Donald Trump probably narrowly won 18- to 29-year-olds. That isn’t what the exit polls say. But if you look at our survey data, voter file data, and precinct-level data, that’s the picture you get.

And if you look at people under the age of 25, every single group — white, nonwhite, male or female — is considerably more conservative than their millennial counterparts. And it even seems that Donald Trump narrowly won nonwhite 18-year-old men, which is not something that has ever happened in Democratic politics before.

So, young people are quite a bit more right-wing than they were four years ago. And a lot of that is replacement. It’s a different set of young people. It turns out, people age.

What’s your sense of why this generation of young people are more conservative than we were? Is it about each cohort’s distinctive formative experiences? In my understanding, political events that transpire during your adolescence and early adulthood can shape your worldview in a durable way. So, maybe the millennial generation came of age during the disaster that was George W. Bush’s second term, and then associated Democrats with an incredibly charismatic two-term president in Barack Obama — while young zoomers associated Democrats with Covid and inflation under Biden? Or is something else at play?

Yeah, I think some of that story is true. Yair Ghitza has an incredible paper that shows that people have formative political years. And you can predict a lot of how conservative someone will be from how popular the incumbent president was when they were teenagers or when they were in their 20s. And so I think that’s definitely true and it’s definitely part of the story. But I think that there’s more to the story than that.

If you look at the millennials, the millennials were more left-wing in a bunch of countries — Canada, the UK, and Europe. I think that there’s a story you can tell: Baby boomers were an incredibly left-wing generation in most places in the world. And millennials were their kids.

But Gen X was really quite a bit more conservative than the Boomers in most countries. And there’s a lot of theories you can make about that — response to the oil shocks, stagflation, neoliberalism. But whatever the reason, Gen X came out more conservative. So I think that part of the story is simply that the current crop of young people had Gen X parents. And in our surveys, if we ask people, “How Democratic were your parents growing up?” zoomers are something like 7 percent more likely to say they had Republican parents than millennials are.

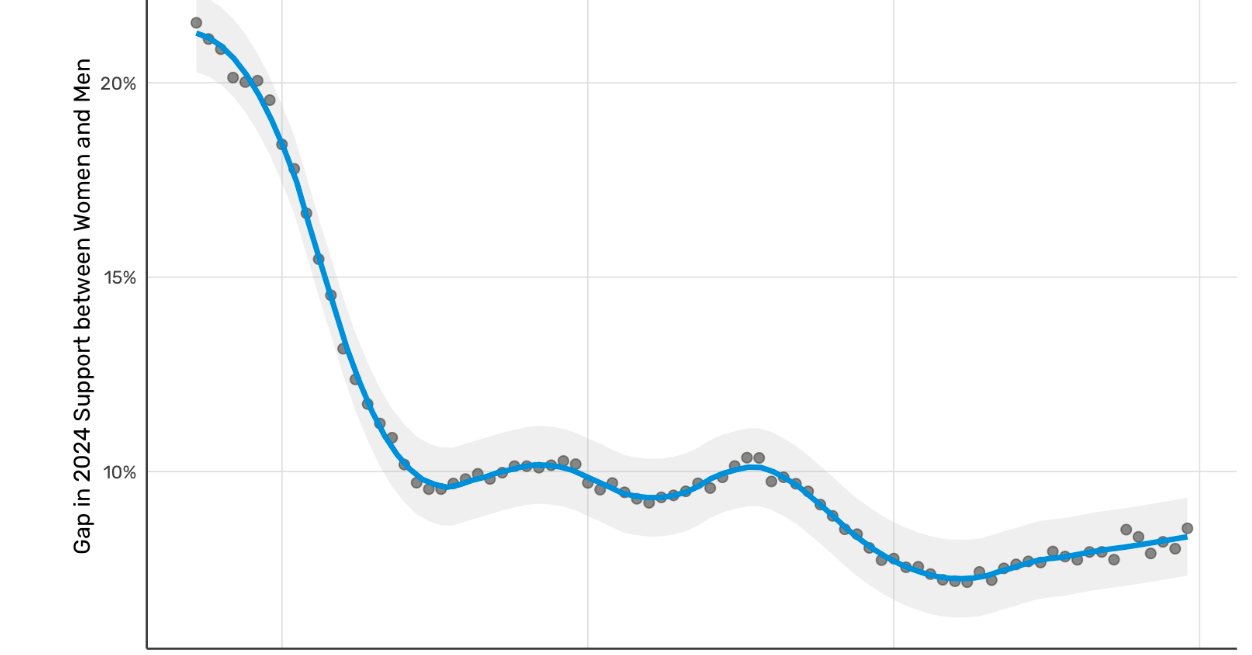

But isn’t part of the Democrats’ problem with younger voters about men, specifically?

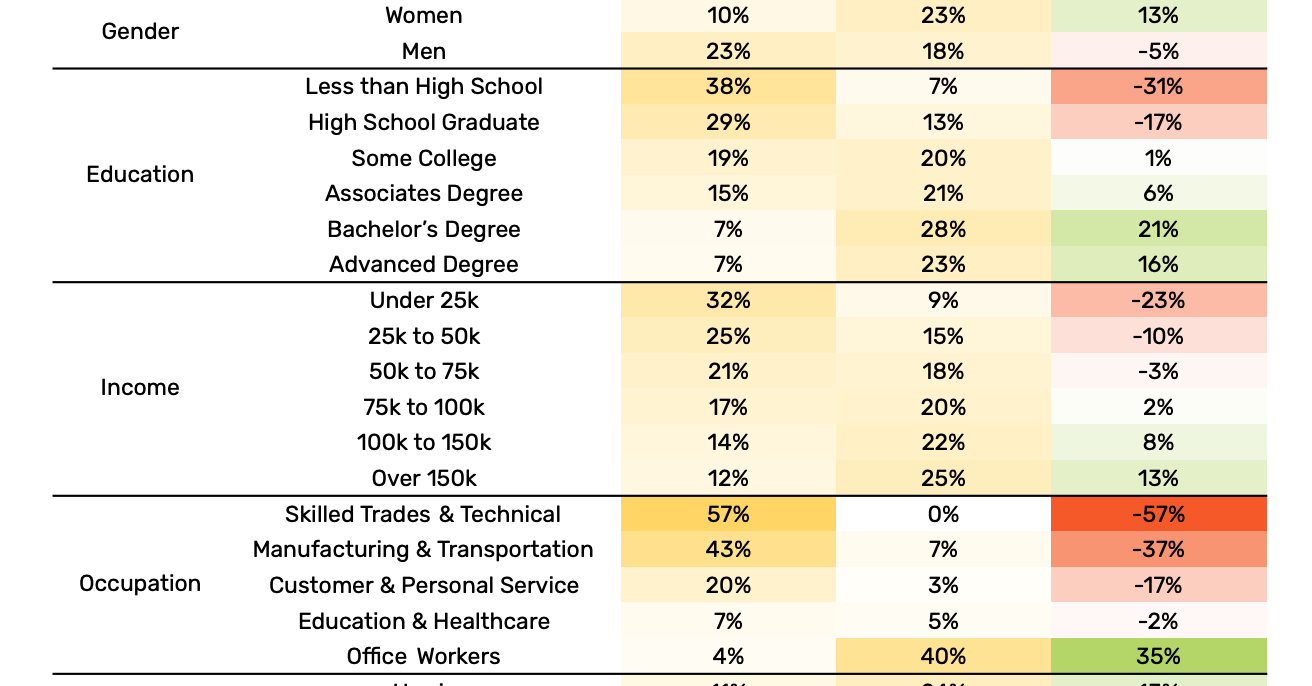

Yeah. There’s also this enormous amount of gender polarization. If you look at the gender gap — just what fraction of the vote Kamala Harris got versus what fraction of the vote Donald Trump got among men and women — for voters over the age of 30, there was about a 10 percent gender gap between men and women. And that’s roughly speaking where it’s been in American politics for most of the last 20 years.

But if you look at voters under the age of 25, the gender gap has doubled in size. And if you look at 18-year-olds, specifically, 18-year-old men were 23 percentage points more likely to vote for Donald Trump than 18-year-old women. And gender polarization seems to be increasing in other countries as well. How it plays out varies from country to country. In Germany, for example, young women voted in very high numbers for Die Linke, the left-wing party there.

A lot of different things could be causing this. But I think that if you look at non-political polling, you can really see evidence that there is wild, cultural change afoot here and basically everywhere else in the online world. In Norway, there’s a poll of high school students where the fraction of young men saying, “gender equality has gone too far” spiked in recent years.

I don’t know necessarily what the answer to that is. But I think it’s important to resist nihilism. These young men who have terrible, retrograde views on politics and gender relations are still pro-choice. They still support universal health care. I think we need our politicians to focus on those fights. But it’s extremely important for other people — who don’t need to win elections — to try to improve the online discourse around these more divisive issues.

Earlier, you referenced the divide between cosmopolitan, college graduates who live in big cities and working-class voters. And you suggested that Democrats need to distance themselves from the sensibilities of highly educated urbanites. I’m wondering if you could get more concrete. Do you think the party merely needs to increase the salience of its best issues by focusing on them rhetorically? Or are there areas where you believe Democrats need to become substantively more conservative?

I think there are two very important things to understand about this election. The first thing is that the Biden administration was extremely unpopular. His approval ratings collapsed after Afghanistan and then continued to decline as prices went up and immigration happened. The budget fights in the fall of 2021 around the reconciliation package were particularly damaging. And then, his approval ratings never really recovered. And so, I think there’s a substantive angle to that.

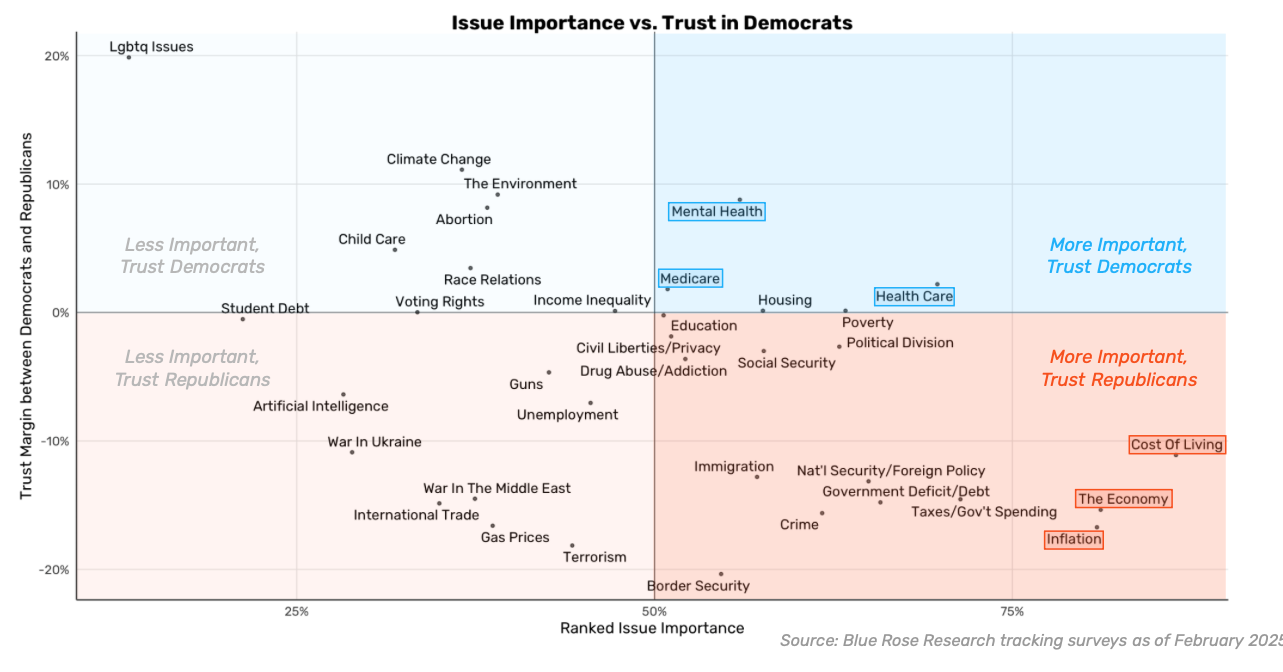

The way that we like to track issues is that we look at 40 different issues and we ask people basically, “How important are these issues?” And then, “What party do you trust more on these issues?”

In 2020, what people cared about the most was Covid and health care. And those were also the issues that people trusted us on the most. And so the thing we had to do was very straightforward: We just had to talk about Covid and health care. That’s what we did. And we won.

But the situation this time was a lot harder. The issue that voters cared the most about was overwhelmingly the cost of living. I really cannot stress how much people cared about the cost of living. If you ask what’s more important, the cost of living or some other issue picked at random, people picked the cost of living 91 percent of the time. It’s really hard to get 91 percent of people to click on anything in a survey.

After the cost of living, it was the size and scope of the federal government, the budget deficit, immigration, crime, and also health care. And people trusted Republicans on these issues by double-digits — except for health care, where we had a 2-point advantage, which was much lower than our traditional advantage on that issue.

I think there’s this nihilism that’s very popular in our industry — that nothing we do, or that the side does, really matters. But in the wake of inflation, voters went from favoring Republicans by about 5 points on the economy to favoring them by 15 or 16. And after Dobbs, voters started trusting the Democrats much more on abortion. Education used to be the Democrats’ strongest issue. But our standing on that collapsed during Covid, and now it’s basically even. So, what people care about and trust us on really is responsive to concrete events that happen in the world. That isn’t 100 percent of the story. There are a lot of other things going on. But what we do and what we say does matter.

To directly answer your original question — about how much of this is changing what our positions are versus messaging — I think the exact details of that vary from issue to issue. But I think that we have to approach this from the position that we are in a deep trust hole. The people that we’re trying to persuade have very different values than we do and have a very different perception of reality. And a lot of these people are very poorly informed and literally do not consume the sources of information that we broadcast to.

And so, there has to be some combination of messaging and outreach and changes in how we approach these platforms, and also probably some substantive changes that address what voters see as an error.

It seems to me that the Democratic Party’s biggest challenge is less how to win the presidency than how to win comfortable Senate majorities. The median US state is much more conservative than America as a whole, and this means that the Senate is heavily biased against Democrats. In 2018 and 2020, Democrats won really strong national victories — and still ended up with just 50 Senate votes in 2021. So, how grim do you think the party’s prospects of winning back the Senate are in the near term, and how can it go about improving those odds?

I think we should start by recognizing how lucky we are. In 2020, we won basically every competitive Senate race. And in both 2022 and 2024, we saw something that I had never seen before, which is that we did a lot better in swing Senate races than we did nationally.

But a lot of that was the other side running terrible candidates. And we can’t count on that happening forever. And even despite that — even despite historically well-run campaigns and historically weak opposition — here we are four years later at 47 Senate seats and with a very difficult path to getting back to 50 even in a wave Democratic year.

And I think that something has to change in order for us to have a majority that’s capable of securing the Senate. But I don’t want to overemphasize the ideological dimension of that. What we really need to do to win in places like Ohio and Iowa is change the brand.

The candidate who outperformed the most in 2024 at the top of the ticket was Dan Osborn in Nebraska. And some of that was just because he ran as an independent. But a lot of it was that he ran an economically populist campaign that focused on issues that people cared about. I think that the moderate and left-wings of the party don’t like each other very much, but they did both like Dan Osborn.

To push back a little on that, Osborn definitely ran a populist campaign. But he also aired advertisements declaring himself “the only real conservative” in the race, attacked his Republican opponent for voting to fund the government, said that he would personally help build Trump’s border wall, and didn’t endorse Kamala Harris.

And so, I feel like there definitely was an element of ideological moderation — or at least, heterodoxy — to his approach. More critically, Osborn refused to say which party he would caucus with once he got to the Senate. And yet, assuming he secretly did intend to caucus with the Democrats, that’s a play you can only run a single time. After that first run, voters know which party you really favor. And it doesn’t seem tenable for Democratic Senate candidates writ large to all pretend that they support Trump or might actually caucus with Republicans. So it’s not clear to me how the Osborn model scales.

I think the main problem is that we tried this strategy in an incredibly red state. I think Trump won Nebraska statewide by 13 points. But there are a bunch of states he won by between 4 and 7 points. The degree of ideological compromise that is necessary to win in a state like Ohio is very different than the degree of ideological compromise that’s necessary to win in a state like Nebraska. And the current status quo is that we have a very low chance of winning in these places at all using the current strategy. But that said, I think that both wings of the party have to make sacrifices in order for us to achieve the coalition that we want.

There’s an interesting tension in your polling: Voters generally say that they would like the Democratic Party to be more moderate, while also saying they favor “major change” and a “shock to the system” because things in America are going poorly. I think many people would look at that and see a contradiction. After all, moderate Democrats generally have less enthusiasm for major policy change — and feel more comfortable with the status quo — than progressive Democrats do.

It’s tricky. On the one hand, voters say they thought that the Democratic candidate was too liberal. But on the other hand, in our randomized control trials, the best testing advertisements were more compatible with progressive critiques of the Harris campaign. The single best testing ad by the Kamala Harris campaign was one where she looked directly into the camera and said something like, “I know the cost of living is too high, and I’m going to fix that by building more housing and taking on landlords who are charging too much.”

And I think you can get into existential debates about what economic populism really is. But I think that the existing research really pointed clearly toward the idea that the electorate wanted economic change — and cared more about that than preserving America’s institutions.

Whatever you want to say about Trump, he has delivered a “shock to the system” — though maybe not the one that voters were hoping for. In your polling, has there been a reduction in support for the president since he took office? If so, where do you see him as being most vulnerable?

Yeah. Trump’s approval rating has dropped since he took office. His ratings on his handling of the economy, which historically was a strong suit for him, have dropped the most, and his handling of cost of living has also gone down by quite a bit. And Elon Musk has become much more unpopular and is now the most unpopular member of his administration by a good deal. Trump and Elon have really spent the first part of their term diving into the biggest weaknesses of the Republican Party — namely, they’re trying to pass tax cuts for billionaires, they’re cutting essential services and causing chaos for regular people left and right, while trying to slash social safety net programs. It’s Paul Ryan-ism on steroids.

I think we have a real opportunity to return to the politics of 2012, in terms of vigorously opposing these very unpopular economic changes that Trump is pushing through.

The presentation that you’ve been giving to Democratic stakeholders takes a sharp turn at the very end. You warn that the party cannot get stuck fighting the last war, and argue that 1) AI is going to cause mass unemployment in the relatively near future, 2) this social and political shock is likely to exacerbate partisan tensions in the US, and 3) Democrats need to start preparing for this scenario. Can you explain your reasoning?

I’m not an AI expert by any means, but AI capabilities are increasing dramatically. And AI experts are very, very bullish on the extent to which AI systems are going to be able to replace some fraction of jobs. The prediction markets say this, too. And I think something that’s really important is that regardless of whether it’s going to happen or not, the public believes it will happen.

If you just ask, “Do you believe that AI will be able to perform most people’s jobs better than humans can in the next 10 years?” 65 percent of the population says yes and 35 percent says no.

And then, when you ask, “Do you think this will be good or bad?” Something like 80 percent of the population believes that this is going to be bad. And so, I think this is something where voters are ahead of the political classes of both parties right now.

I think when you try to speculate about something like this, it’s important to recognize that nothing like this has ever really happened before, so it’s hard to make predictions. But we worked with two economists, Jonathan Hersh and Daniel Rock, who have made fine-grained estimates of which jobs are going to be the most affected by AI and which the least. And their work indicates that this will impact college-educated people more than working-class people for the simple reason that LLMs are advancing more quickly than robotics is. And AI will also have a bigger impact on employment in cities and suburbs than in rural areas. And it will impact women more than men.

And I really worry that this may accelerate these cultural divides that politics have been centered on in the last decade, in a way that could be unproductive and dark. In a lot of ways, this could be the biggest culture war fight of the century. And I don’t pretend that I have the answer on what we should do. But with Covid, we had this sudden shock and our response just reinforced the dysfunctional cultural divides that had already opened up in 2016. And those effects have persisted and made it harder for us to win elections today. But unlike with Covid, we have a real chance of seeing this next shock a year or two ahead of time. And we really have to think about this proactively and not just dig our heads into the sand.

Recent Comments