The past few years have violated many of my assumptions about human progress. Twenty-year-olds are going MAGA. More and more Americans say that women should return to their “traditional” roles in society. For some reason, we have decided to gamble with bringing back once-eradicated deadly diseases.

And now, add to the list: Cow’s milk is back. Sort of.

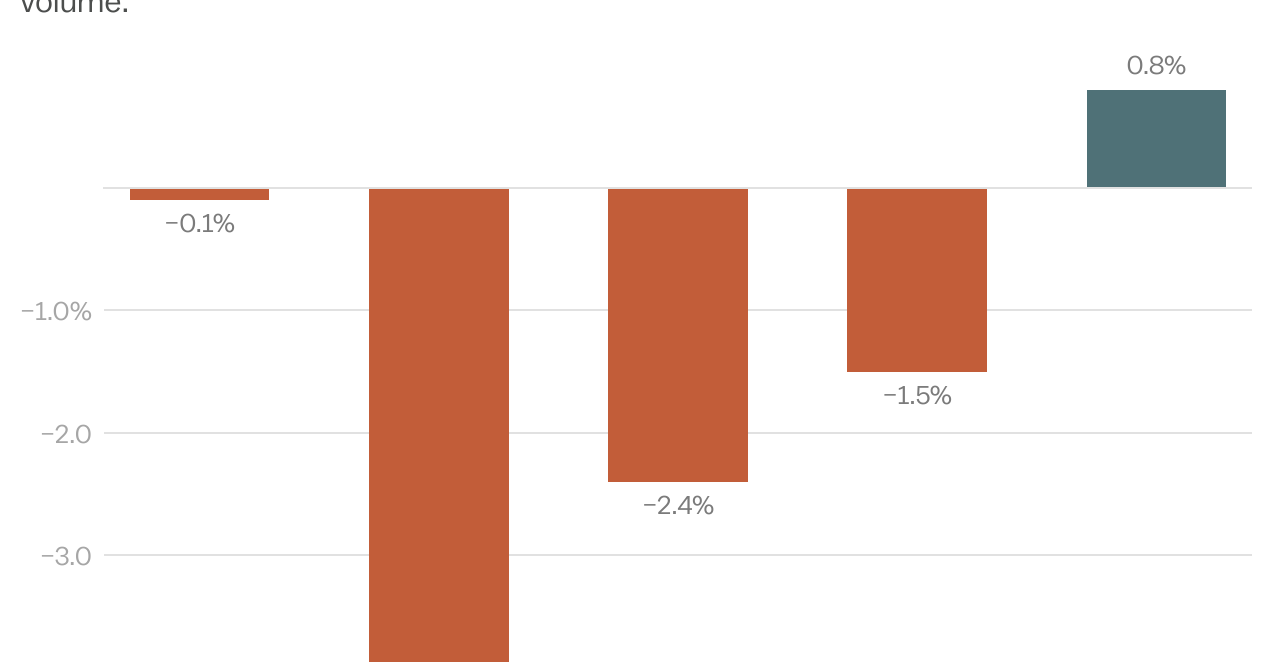

Last year, US dairy producers sold about 0.8 percent more milk than in 2023, according to US Department of Agriculture (USDA) statistics, the first year-over-year increase since 2009, when milk prices were historically low. That may not sound like much, but it’s a big deal for the dairy industry, which has seen a sustained drop in both per capita and total US milk consumption over the last few decades. Raw milk, which has not been pasteurized to kill pathogens, has seen double-digit growth, a concerning trend given its potential to spread life-threatening infections, though it still makes up a very small share of overall milk sales.

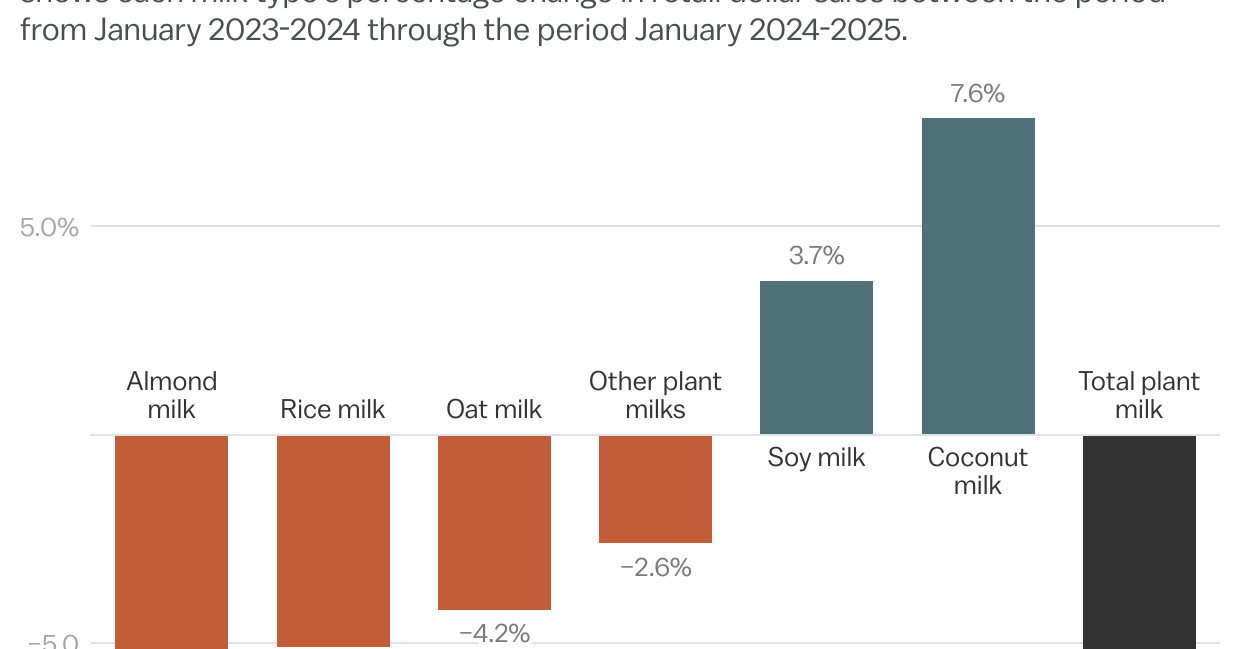

Meanwhile, non-dairy milks — the kind made from soybeans, oats, almonds, and other plants — have stumbled, declining by about 5 percent in both dollar and unit sales over approximately the last year, according to data shared with Vox by NielsenIQ and data reported elsewhere from the market research firm Circana.

A small uptick in cow’s milk intake is, obviously, not tantamount to the calamities that have been unleashed over the last six weeks in American politics. But it does likely sprout, at least in part, from the same vibe shift that’s given us butter-churning, homestead-tending tradwives, an unscientific turn against plant-based foods, and a movement to destroy public trust in vaccines.

After achieving ubiquity in the 2010s and early 2020s, plant-based milks may have lost their cool, nonconformist quality — much like how, after more than a decade of liberal cultural supremacy, embracing authoritarian revanchism now feels like countercultural rebellion.

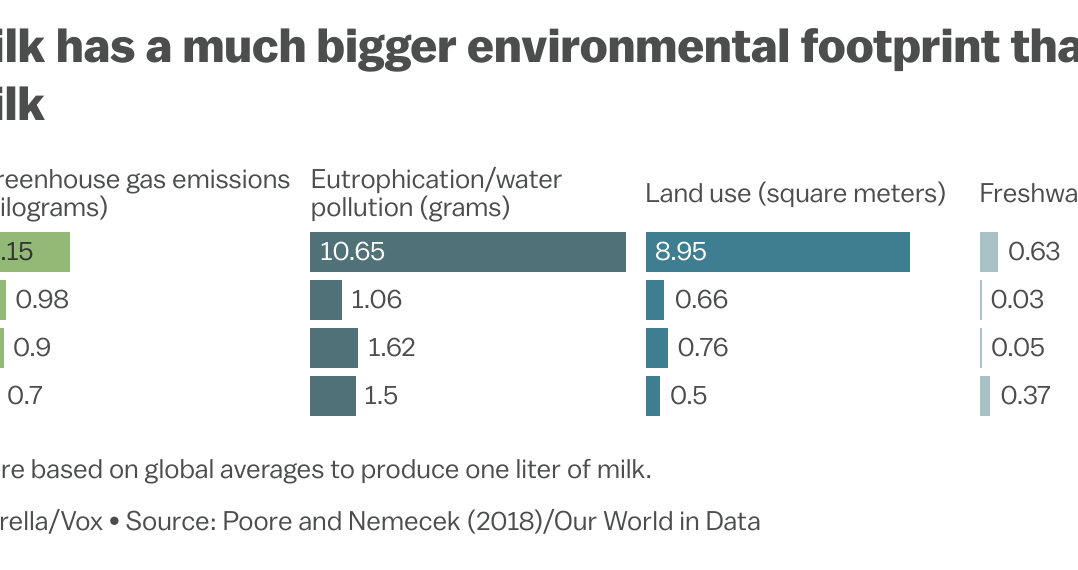

The problem is that cow’s milk is not, unfortunately, just a harmless dietary preference — it’s land-intensive, water-intensive, climate-warming, and incredibly cruel to cows. Dairy cows contribute more than 10 percent of US methane emissions, a super-potent greenhouse gas, and their land use, while not nearly as great as that of beef farming, is still high, occupying land that could otherwise be freed up for carbon-sequestering ecosystems. To mitigate climate change, our dairy consumption needs to go down, not up.

It’s too early to tell whether the growth in milk sales is a temporary blip or a genuine turning point; Dotsie Bausch, executive director of Switch4Good, a group that advocates for moving away from dairy consumption, told me she’s optimistic it’s the former. And all this comes amid another important shift: America’s top coffee chains, including Starbucks, Dunkin’, Dutch Bros, Tim Hortons, and Scooter’s — very large buyers of milk — have all in recent months dropped their extra charges for adding plant-based milks to drinks, a change that animal rights groups, led by Switch4Good, had demanded for years.

That change makes it anywhere from 50 cents to $2 less expensive to choose plant milks over cow’s milk, and will likely nudge some customers to choose more planet-friendly plant-based options. Still, while economic incentives do matter for milk consumption, as we’re increasingly seeing, they’re not the whole story.

Why dairy milk is becoming more popular

If you really think about it, it’s weird that we drink dairy milk — the milk that cows, like all mammals, make for their babies.

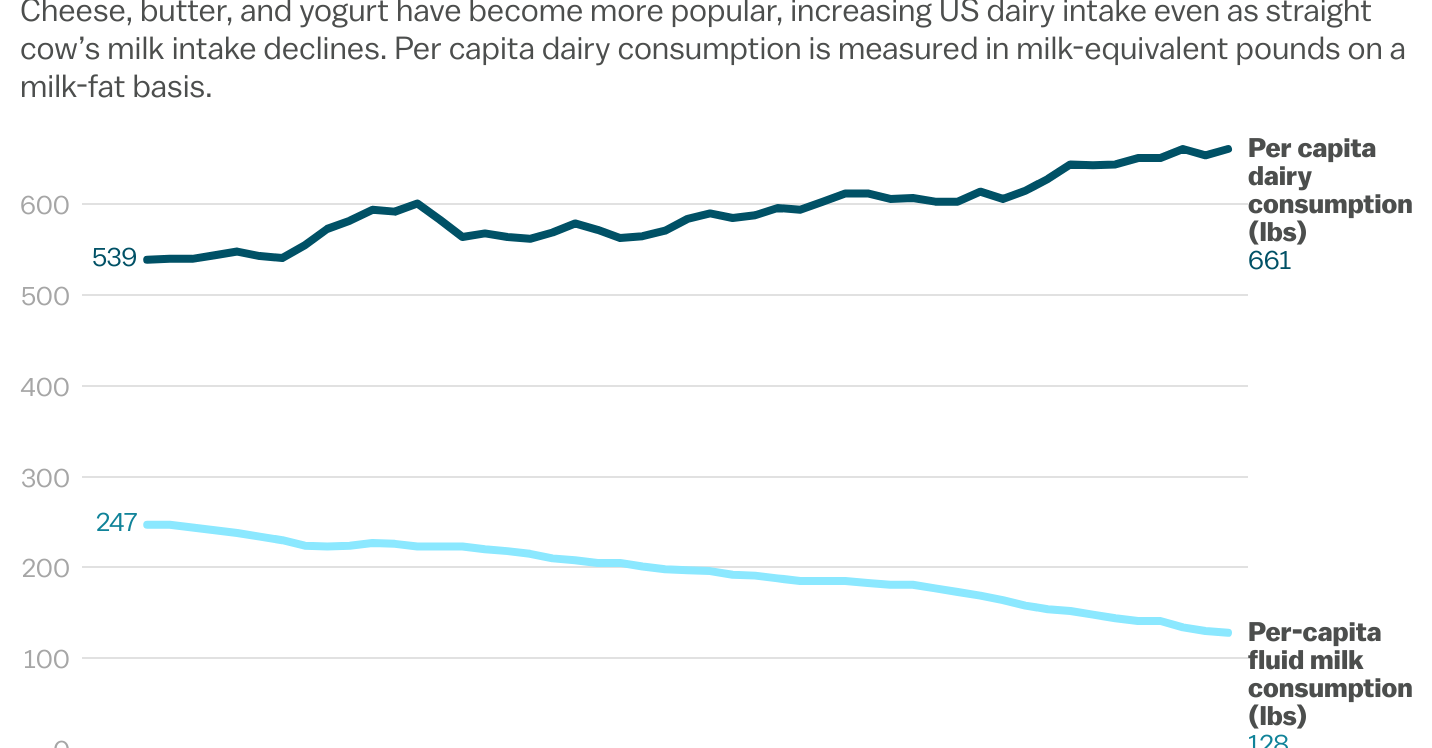

There’s no compelling reason to think humans need to drink milk after infancy, much less the milk of another species. Nevertheless, thanks to many years of “pseudo-scientific theories that exalted drinking-milk to permanent and unquestioned superfood status,” as culinary historian Anne Mendelson put it in her book Spoiled: The Myth of Milk as Superfood, cow’s milk consumption became practically compulsory in the US, peaking in 1945 at 45 gallons per person, or about two cups per day. And that’s only counting straight cow’s milk, not other dairy products made from it like cheese, butter, or ice cream, which added a lot more — ice cream consumption peaked in 1946, at 23 pounds per person.

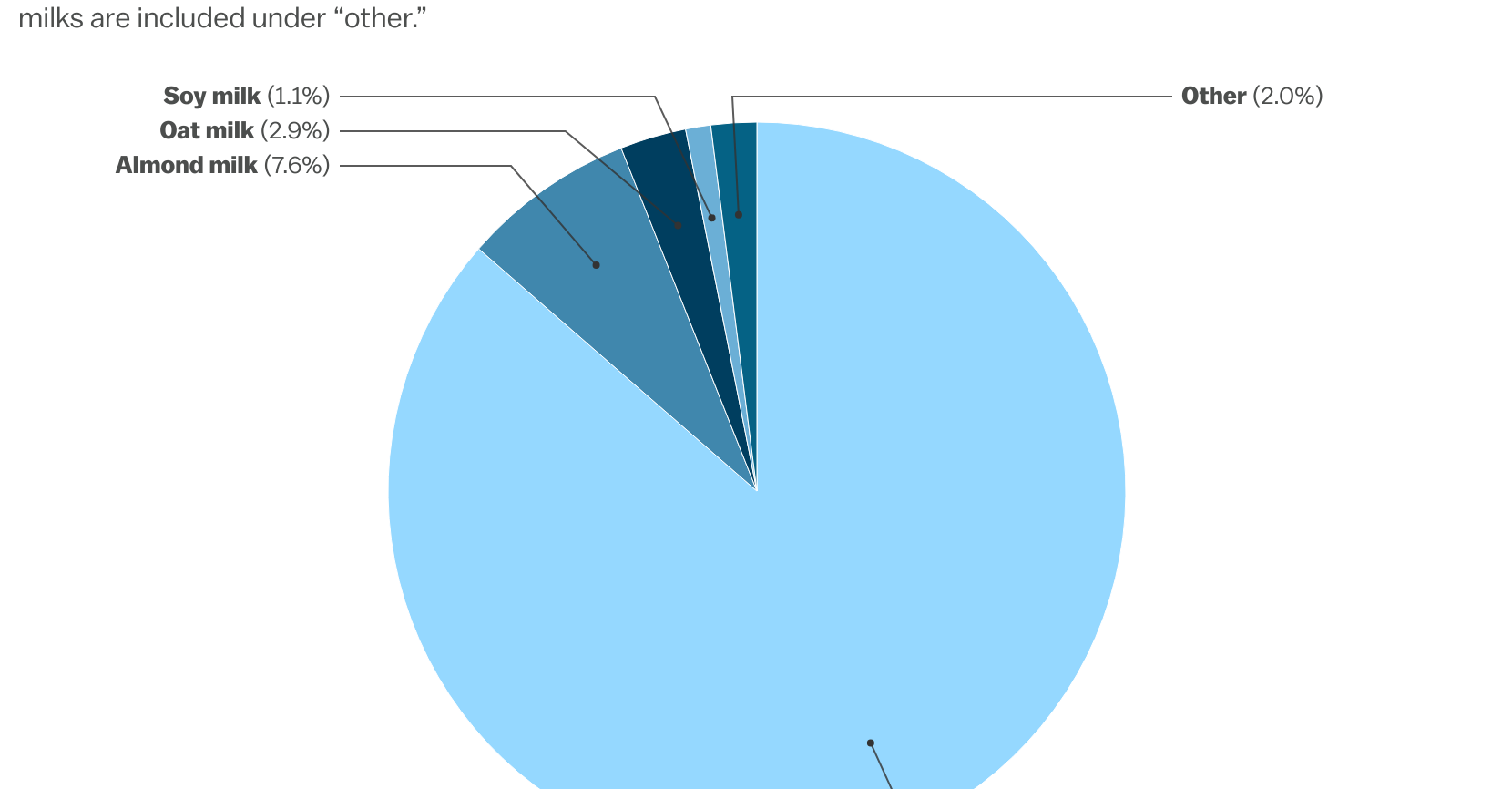

After World War II, fluid milk intake plummeted, falling to less than half a cup per person per day on average in 2019. It’s important to keep these trends in perspective, however: More than 90 percent of US households still buy cow’s milk, while less than half buy plant-based milk; plant milk sales are still way lower than sales of cow’s milk. And even as cow’s milk in fluid form became less popular, overall dairy intake in the US has only increased since the 1970s, driven by growing consumption of cheese, butter, and yogurt.

So why might drinking cow’s milk be coming back? The most persuasive hypotheses boil down to three things: price, perception, and protein.

The first one is pretty obvious: Consumers are angry about inflation, struggling with high grocery bills, and switching to lower-cost options. Conventional dairy milk — the kind that makes up more than 90 percent of the cow’s milk market and comes in clear, hard-plastic jugs with brightly colored caps — is generally cheaper than any plant-based milk you can get. The cheap soy milk I buy is still more than twice the cost by volume of the cheapest cow’s milk at my grocery store.

If you know anything about how resource-intensive cow’s milk is to produce, its low cost might seem counterintuitive. Part of that is because the costs are externalized elsewhere: Cows have been bred to produce immense volumes of milk over the last century, which has brought down the cost while taking a heavy toll on their welfare. Most milk today comes from mega dairies, which benefit from economies of scale by confining thousands or even tens of thousands of cows in one place, but these operations are known for spreading pollution and foul odors to nearby communities.

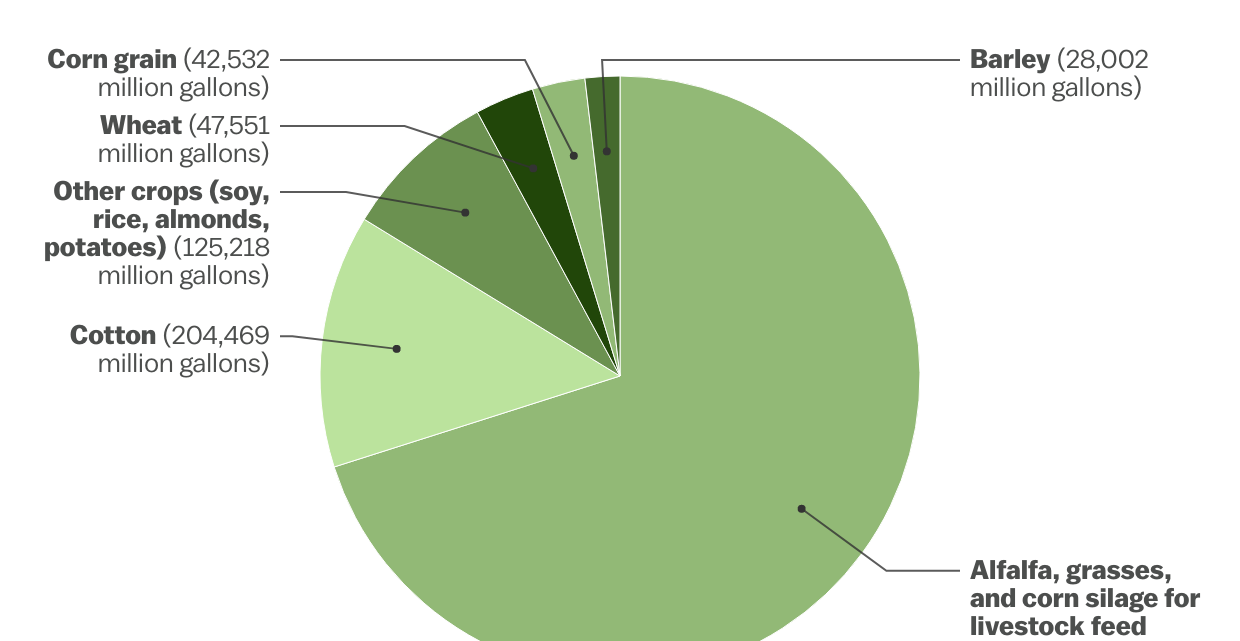

Dairy is also much higher in greenhouse emissions than plant-based foods with comparable nutrition, and much more water-intensive, contributing to water scarcity in arid Western states like California, the nation’s top dairy producer. But the dairy industry, as well as those that grow crops to feed cows, gets to use all that water at low cost, a classic “tragedy of the commons,” UC Davis agricultural economist Richard Sexton told me.

Soy milk, while far less resource-intensive than dairy, has higher manufacturing costs, and hasn’t benefited from the decades of US government-subsidized R&D that have lowered the cost of cow’s milk, nor from the dairy industry’s scale efficiencies. The cost of the soy used to make soy milk is also shaped by competition with other, much larger, uses of soybeans, Sexton said. Most soy grown in the US is fed to farmed animals, while another chunk is used to make subsidized biofuels.

Why soy milk rules

Soy milk, which has been consumed in East Asia for centuries, is almost too good to be true — but at just 1 percent of the US milk market, it doesn’t get enough credit. It’s packed with protein and (assuming you get a fortified variety) essential nutrients, low in saturated fat, and much lower in sugar than milk.

The federal government’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans recognize fortified soy milk as an appropriate substitute for cow’s milk. I think it’s an even better choice, kinder to both the planet and to cows. If you haven’t had it before, soy milk might taste different from what you’re used to, but it has a satisfying, full-bodied texture and nutty flavor. And don’t worry about whatever you may have heard about the supposed dangers of soy — it’s been debunked. It’s literally a bean, and we can all use more of that in our diets.

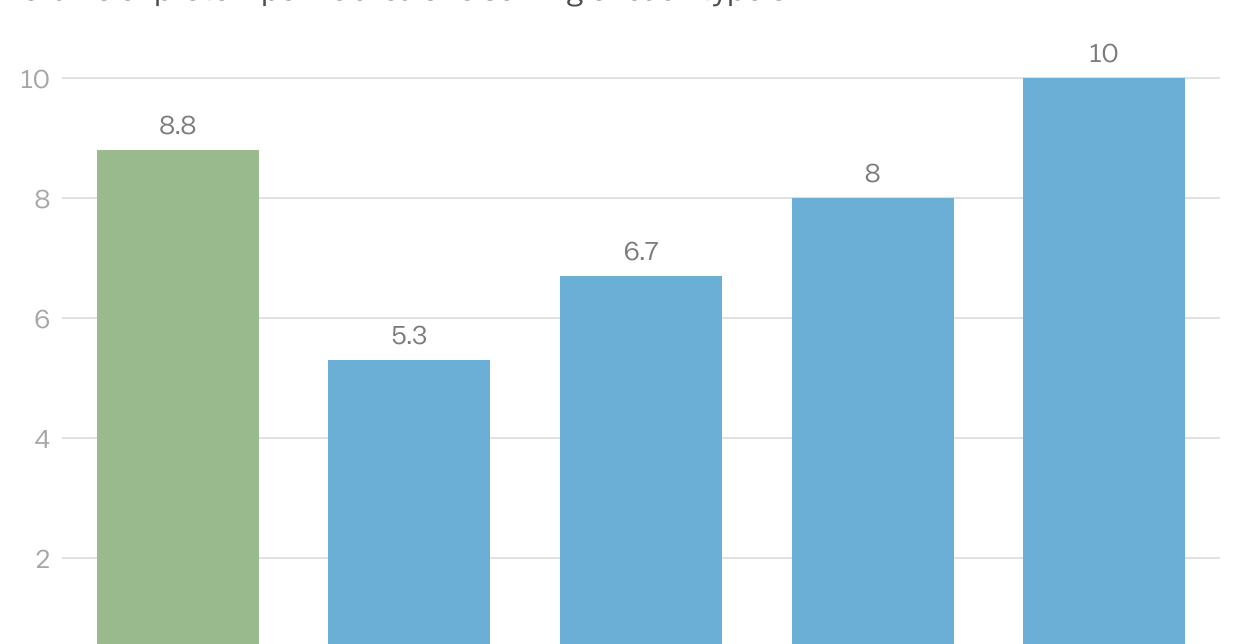

But look closer at the data, and the price explanation for dairy milk’s rebound becomes a lot more complicated. Organic milk sales grew by 7 percent by volume from 2023 to 2024 — about 19 times faster than conventional milk did over the same period. And organic cow’s milk is significantly pricier than conventional; often, it’s more expensive than plant-based milks. Lactose-free milk, which is also costlier than regular milk, saw huge gains, too, with many new buyers switching from less-expensive plant-based milks.

One factor might simply be taste and feel, Chris Costagli, vice president for food insights at NielsenIQ, told me. Consumers seem to be trying to incorporate more fats in their diets: Rich, full-bodied whole milk, which has been rising in popularity as low-fat milks decline, may be gaining appeal compared to almond milk, the most popular plant milk, which is runny and low in calories.

And then there’s the hazier but crucial element of consumer perceptions — in other words, vibes.

Americans are increasingly skeptical of so-called ultra-processed foods, an ill-defined, unrigorous concept that I covered back in December. Most plant-based milks fall into that category, putting them on the wrong side of today’s culture war, which has swung toward the regressive and anti-modern.

Consumers find the ingredient lists of cow’s milk — which is often just “milk” and added vitamins — simpler and easier to understand than those of plant milks, Costagli said, and they also might feel that they’re getting a better value. “The first ingredient on dairy milk is milk. The first ingredient on plant-based is water,” he said. That’s true — but cow’s milk is also overwhelmingly comprised of water. A more detailed ingredient list might look like this: Water, milk fat, casein, whey, lactose, vitamins, minerals, enzymes, estrogen, progesterone, Insulin-like Growth Factor 1. Novel foods suffer from the perception of being “unnatural” and mechanized regardless of their actual health impacts.

I’m reminded of what 20th-century philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” arguing that in an era of mass production, objects lose their “aura,” or uniqueness and authenticity. Cow’s milk, particularly the kind that’s marketed as unadulterated and close to the source, like organic, appeals to a sense of lost aura by promising to reconnect consumers with something ancient and primal — a living, breathing animal, the very opposite of a machine.

But this fatally misunderstands the nature of modern dairy farming, which one could reasonably define as the process of turning an animal into a milk-making machine. Organic dairy does have some standards that are better for animal welfare, including a requirement for cows to have access to pasture for at least 120 days per year, although organic dairy has been gamed and industrialized to such an extent that it often resembles conventional mega dairies.

More fundamentally, though, there’s no guarantee that organic dairy cows are treated humanely because both organic farms and conventional mega dairies rely on the same business model: Putting cows through repeated, taxing cycles of insemination, pregnancy, and lactation, separating them from their calves so that humans can take their milk, and then sending them to slaughter at a young age when their health and productivity decline. Organic dairy is not meaningfully better for the environment, either.

Got soy milk?

There’s one more factor we need to consider to understand what’s happening in the cow’s milk market: America’s obsession with protein. Most types of plant milk, including oat, almond, and coconut, are significantly lower in protein than cow’s milk. That might explain why sales of soy milk — which is higher in protein as a share of calories than either whole, reduced fat, or low-fat cow’s milk — have remained stable, while low-protein almond milk has seen the steepest declines.

Some companies have even introduced “ultra-filtered” cow’s milk that’s higher in protein than regular milk. The Coca-Cola-owned milk brand Fairlife, which has seen massive growth in recent years thanks to the popularity of its high-protein products, was recently the subject of an undercover investigation by the animal advocacy group Animal Rescue Mission. The group found appalling animal abuse at two Fairlife supplier farms in Arizona, including cows and calves being beaten, dragged, chained, and shot. A 2019 investigation found similar abuse at another Fairlife supplier, and Coca-Cola in 2022 settled lawsuits alleging that it falsely advertised Fairlife milk as coming from humanely raised cows.

“The mistreatment of animals depicted in the recent videos is unacceptable. Effective immediately, our supplier, United Dairymen of Arizona (UDA), has suspended delivery of milk from these facilities to all UDA customers,” Fairlife told Vox in a statement. “We have zero tolerance for animal abuse. Although we operate as milk processors and do not own farms or cows, we mandate that all our milk suppliers adhere to stringent animal welfare standards, and we expect nothing less.”

So what kind of milk should people drink if they care about nutrition and animal welfare? The perfect milk for most people is made of soybeans.

Soy milk is not just high-protein, but also lower in saturated fat than any type of cow’s milk except skim, much lower in sugar (make sure you get an unsweetened variety), and even has fiber, which, unlike protein, Americans are actually deficient in. If you get a fortified variety, like the leading soy milk brand Silk, you also get calcium, vitamin D, and other essential nutrients.

If you’re accustomed to cow’s milk, soy might just taste different. Myths about adverse health effects from soy have been debunked; unless you have an allergy, there’s no reason to be afraid of it. To the contrary, soy is simply a bean, and one of the best sources of protein out there.

Soy milk is also unequivocally better for the environment than dairy, isn’t made with animal abuse, and as a plus, won’t help start the next pandemic. The US federal dietary guidelines recognize fortified soy milk as an appropriate substitute for cow’s milk.

Despite this, it is, strangely, the official policy of the US government to promote cow’s milk consumption and protect it from changing consumer preferences — an outdated vestige of 20th-century agricultural policy that punishes plant-based foods at a time when we most need them.

Seen in this light, the perceived resurgence of cow’s milk may really just be one more example of the re-entrenchment of the status quo. Although it’s seeing a bit of a renaissance, cow’s milk has never not been mainstream. The truest form of cultural rebellion has always been to simply avoid it.

And please, whatever you do, don’t drink raw milk.

This story originally appeared in the Processing Meat newsletter. Sign up here!

Recent Comments