Since the start of 2025, over 27 million egg-laying hens — 9 percent of the entire national flock — have died from the bird flu or have been (horrifically) killed to slow the spread.

It’s led to egg shortages and price spikes, with a carton of a dozen eggs today costing double what it did in early 2022, when this latest bird flu outbreak began.

Because of its impact on grocery bills, the mass killing of egg-laying hens has received far more attention than the more routine cruelties in the egg industry. But each year, whether there’s a bird flu outbreak or not, far more chickens are brutally killed for an entirely different purpose.

The egg industry hatches around 650 million birds annually, but because half of them — the males — can’t lay eggs, egg companies kill them the day they’re born. They’re typically shredded alive or gassed with carbon dioxide. Undercover investigations into hatcheries by animal rights groups have revealed this dark but little-known side of the business. Even for the already cruel factory farm industry, it’s created an image problem for egg producers.

But here’s the good news: Technology to end this grisly practice is finally coming to the US.

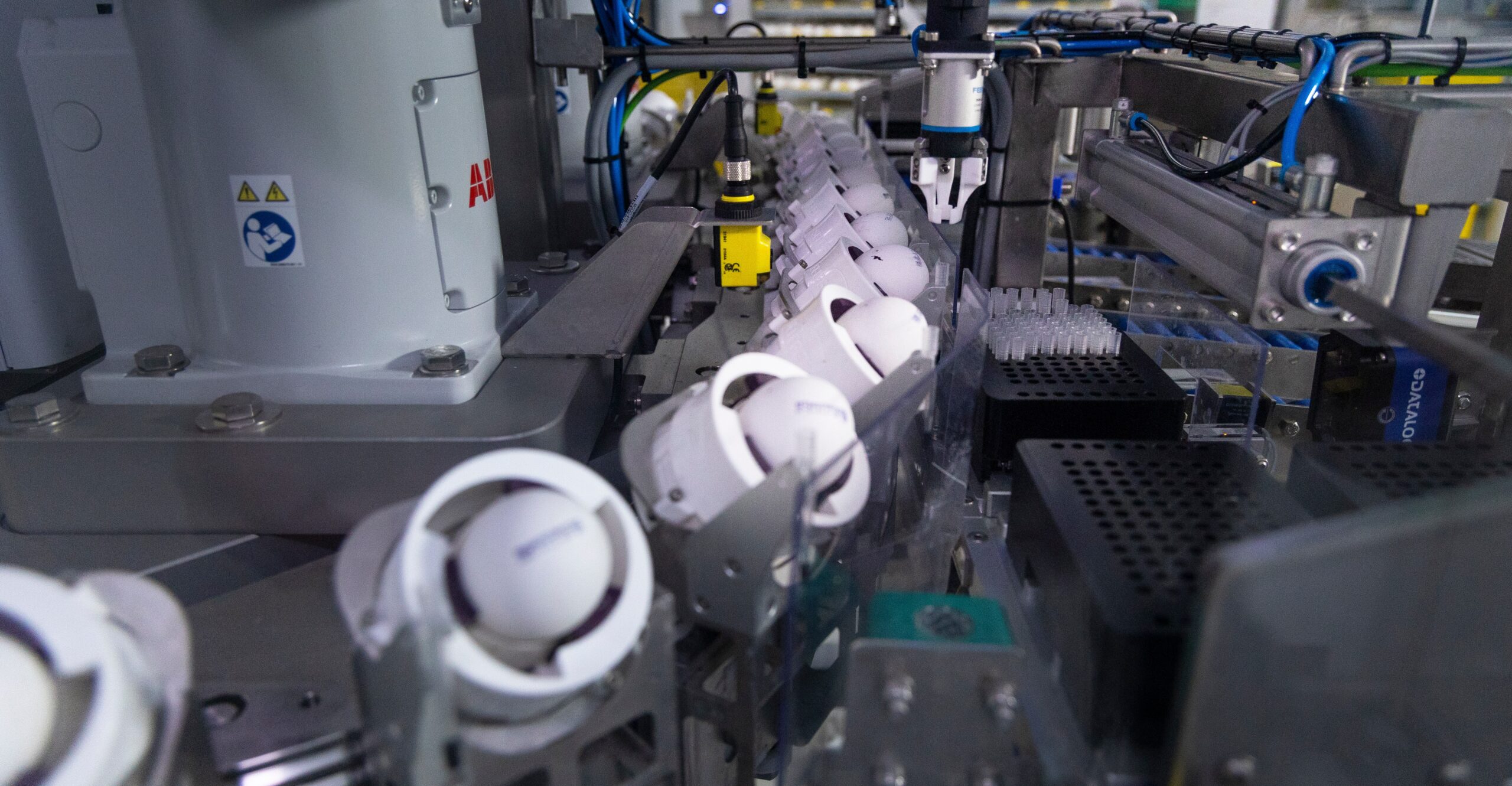

Known as “in-ovo sexing” (“in-ovo” is Latin for “in the egg”), the technology detects the sex of a chicken while still in the egg so that companies can dispose of them before they hatch to avoid the shredding and gassing. There are two main ways to do it: using hyperspectral imaging to see inside the egg without puncturing it, or making a tiny hole in the egg and extracting fluid for rapid analysis. And the technology hardly raises the cost of production, at just a few pennies per carton.

Over the last few years, in-ovo sexing has swept the European egg industry, covering approximately 20 percent of the continent’s egg supply as of April 2024, according to an analysis by Innovate Animal Ag, a nonprofit that advocates for technological solutions to animal welfare problems. The shift was spurred by a mix of technological advancements, pressure from animal welfare groups and consumers, and several country-level laws that ban killing male chicks.

In the next few years, the technology might soon be embraced by the US egg industry.

Last December, the nation’s largest egg hatchery, located in Iowa, hatched its first set of in-ovo sexed chicks using a machine from the German company Agri Advanced Technologies that can scan more than 20,000 eggs per hour. Eggs from those hens will be sold by NestFresh Eggs, an upmarket company that sells pasture-raised and free-range eggs, and will hit grocery store shelves this summer. Agri Advanced Technologies has also installed an in-ovo sexing machine at a hatchery in Texas.

Further reading

The biggest animal welfare success of the past 6 years, in one chart

One state’s flawed, desperate new plan to fix its egg shortage

Weeks later, another European in-ovo sexing company called Respeggt announced plans to install a machine at a large hatchery in Nebraska, which will be operational this spring and will supply to the premium egg company Kipster. Respeggt is in negotiations to install more of its machines at US hatcheries. And last month, Walmart, America’s biggest grocery retailer, asked its egg suppliers to work on in-ovo sexing technology. Another free-range and pasture-raised egg producer, Happy Egg, has committed to use in-ovo sexing technology but hasn’t yet started.

The grisly practice of mass killing male chicks may not end altogether anytime soon, as only a handful of high-end egg producers have adopted or committed to in-ovo sexing so far, and none of the big players have. But it’s often the premium companies that are the first movers in improving animal welfare and, later, large companies follow.

“It will be interesting how [the biggest egg] producers, like Cal-Maine, for example, or Rose Acres…will behave, what they will do,” said Agri Advanced Technologies managing director Jörg Hurlin.

Robert Yaman, CEO and founder of Innovate Animal Ag, said egg companies understand this is the direction the egg market is headed. “When we have conversations with folks in the industry, I think there is a real sense that this is inevitable,” he said. “This is the future.”

Recent Comments